Umbrella effects in cartel damages litigation: What are they, and when could parties claim for them

Share

Umbrella effects arise when non-cartel firms inadvertently benefit from a cartel’s price increases, allowing them to raise their own prices under the cartel’s “umbrella”. In this article, Tara Ghobadian, Patricia Lorenzo and Bernardo Sarmento [1] explore these umbrella effects, from when they are most likely to arise to why they matter. Whilst damages claims concerning umbrella effects are often overlooked in cartel damages litigation, the authors highlight that the application of economic theory and econometric analysis can help claimants to establish causation, demonstrate reasonable foreseeability, and quantify harm in court. They argue that applying economics in this way can help courts recognise the validity of such claims and facilitate the compensation of victims.

Introduction

When companies collude to raise prices, the benefits may not be limited to the colluding parties. Their cooperation may inadvertently benefit non-cartel firms who, relieved of competitive pressure, can profitably increase prices in the presence of the cartel. This phenomenon, known as “umbrella effects”, is crucial for understanding the full extent of harm caused by collusive practices.

While it is commonly accepted that the goal of follow-on damages cases should be to compensate victims for the full harm caused by infringements, few parties bring damages claims for umbrella effects. In Europe, at least, there is no barrier in principle. But in practice, parties may be sceptical that courts will accept damages claims linked to umbrella effects, citing challenges in proving a causal link between cartel actions and the pricing of non-cartel firms.

This scepticism is misplaced. Permissible claims must demonstrate that the claim has a causal link to the cartel, and was reasonably foreseeable to the participants. Economic theory helps assess both. It can provide guidance as to when umbrella effects can and are likely to occur: where products are more homogeneous, cartel market coverage is extensive, and firms face barriers to expanding production in response to rising demand. Econometric methods can be used to quantify such effects, using the same tried and tested tools applied to quantifying harm to direct customers. Courts should take claims arising from umbrella effects seriously when supported by robust evidence.

The remainder of this article explores these issues in detail. We examine the concept of umbrella effects and their legal recognition, analyse the economic conditions that make them more and less likely, and outline practical methods for quantifying their impact.

What are umbrella effects?

Umbrella effects occur when companies outside a cartel benefit from its practices, effectively operating under protection of the “cartel’s umbrella”.[2],[3]

When cartel members engage in anticompetitive practices like price fixing, they can create conditions that allow non-cartel firms to profitably raise their prices, a phenomenon known as “umbrella pricing”. [4] These firms may, knowingly or unknowingly, charge higher prices than they could have under competitive conditions. This leads to higher prices for customers who purchase from non-cartel firms – so-called “umbrella customers”. [5]

For example:

a. Three manufacturers (Firms 1, 2 and 3) initially compete on price, each setting prices to maximise profits taking into account the prices charged by the other two firms.

b. Firm 1 and Firm 2 then form a cartel, colluding to raise prices. In response, some customers consider switching to Firm 3, seeking lower-cost alternatives to the now more expensive cartel options.

c. Faced with this surge in demand, Firm 3 might find it profitable to increase its prices to levels higher than before the cartel existed.

d. Under the protection of the cartel's umbrella, Firm 3 is enabled to engage in umbrella pricing.

While these umbrella customers clearly incur losses due to the cartel, their ability to claim compensation depends on the relevant legal framework – we discuss this next. [6]

The legal perspective on umbrella effects

The European Commission’s Directive 2014/104/EU (“Damages Directive”) [7] affirms the right of victims of competition law infringements to claim compensation. However, it provides no clear guidance over whether claimants can hold cartel members liable for umbrella effects, leaving the decision largely down to national courts.

The European Union first formally acknowledged umbrella effects in the European Court of Justice’s (“ECJ”) 2014 Kone decision. The court ruled that victims of umbrella pricing caused by the “elevator cartel” were eligible to claim compensation from cartel members [8] if a causal link existed between the cartel’s actions and the harm suffered. [9] Specifically, the court held that such a link exists if the losses were reasonably foreseeable to the cartel members.

While the ECJ’s reliance on reasonable foreseeability provides some guidance on the treatment of umbrella effects, it leaves room for interpretation at the national level. In its landmark “retail cartel” judgement, Germany’s Federal Court of Justice (“FCJ”) lowered the standard of proof for demonstrating causation in cartel damages claims. In this judgement the court also clarified that the causal relationship between the cartel and umbrella effects is relevant for assessing potential damages claims against cartel members. [10]

The extent of evidence required to prove causation, and whether such evidence would be accepted by lower courts, remains to be seen. However, despite courts recognising the liability of cartelists for umbrella pricing damages, often few of these claims are pursued – perhaps because their track record in national courts has been mixed. For example, despite the ECJ’s Kone ruling, the Austrian Supreme Court denied damages, reasoning that pricing decisions of the non-cartel firms were not foreseeable to cartel members and lacked sufficient causal links. [11] Where umbrella damages have been awarded, it is unclear on what basis the court was willing to accept causality. The Paris Court of Appeal for example accepted umbrella effects in its 2021 dairy cartel ruling as a definite loss suffered, citing evidence of price increases by non-cartel members. [12]

In the United States, courts are divided. Some accept claims for umbrella pricing, but many reject them on the grounds that quantifying such damages is too conjectural and hence difficult to prove. [13] The Supreme Court has yet to weigh in, leaving the legal standing of umbrella plaintiffs uncertain. [14]

Despite differences across jurisdictions, we would expect that following the ECJ’s Kone ruling, determining the relevance of umbrella effects in a case would require an assessment of whether the cartel could have reasonably foreseen losses to umbrella customers. Foreseeability is considered more likely when (i) the cartel members cover a significant proportion of the relevant market, and (ii) the market is homogenous and transparent. [15] These conditions not only make foreseeability more plausible but also increase the likelihood of umbrella effects arising in the first place. In this sense, the foreseeability legal requirement is closely linked to the economic assessment of the likelihood of effects. When umbrella effects are considered foreseeable, the next challenge is quantifying them.

From an economics perspective, testing and demonstrating that there is a causal and reasonably foreseeable link between the cartel and umbrella effects is not as challenging as it may appear from the incipient case law. In the next sections, we explore the two key questions where economics can be of help: when are umbrella effects likely to arise, and how can they be quantified?

When are umbrella effects likely to arise?

The existence and magnitude of umbrella effects depend on the specific market conditions which affect the strategic reactions of non-cartel firms to the actions of a cartel.

Umbrella effects can only arise if the cartel’s direct customers have suffered an overcharge. Assuming this is the case, some of the cartel’s demand will shift to substitute products, increasing the demand for the non-cartel firms’ offerings. In response, these firms can employ one of two strategies: (i) maintain low prices to capture a larger share of the market, or (ii) raise prices under the protection of the cartel’s umbrella. [16] Importantly, these reactions reflect economically optimal responses to changes in demand and should not be viewed as wilfully exploitative free-riding. [17]

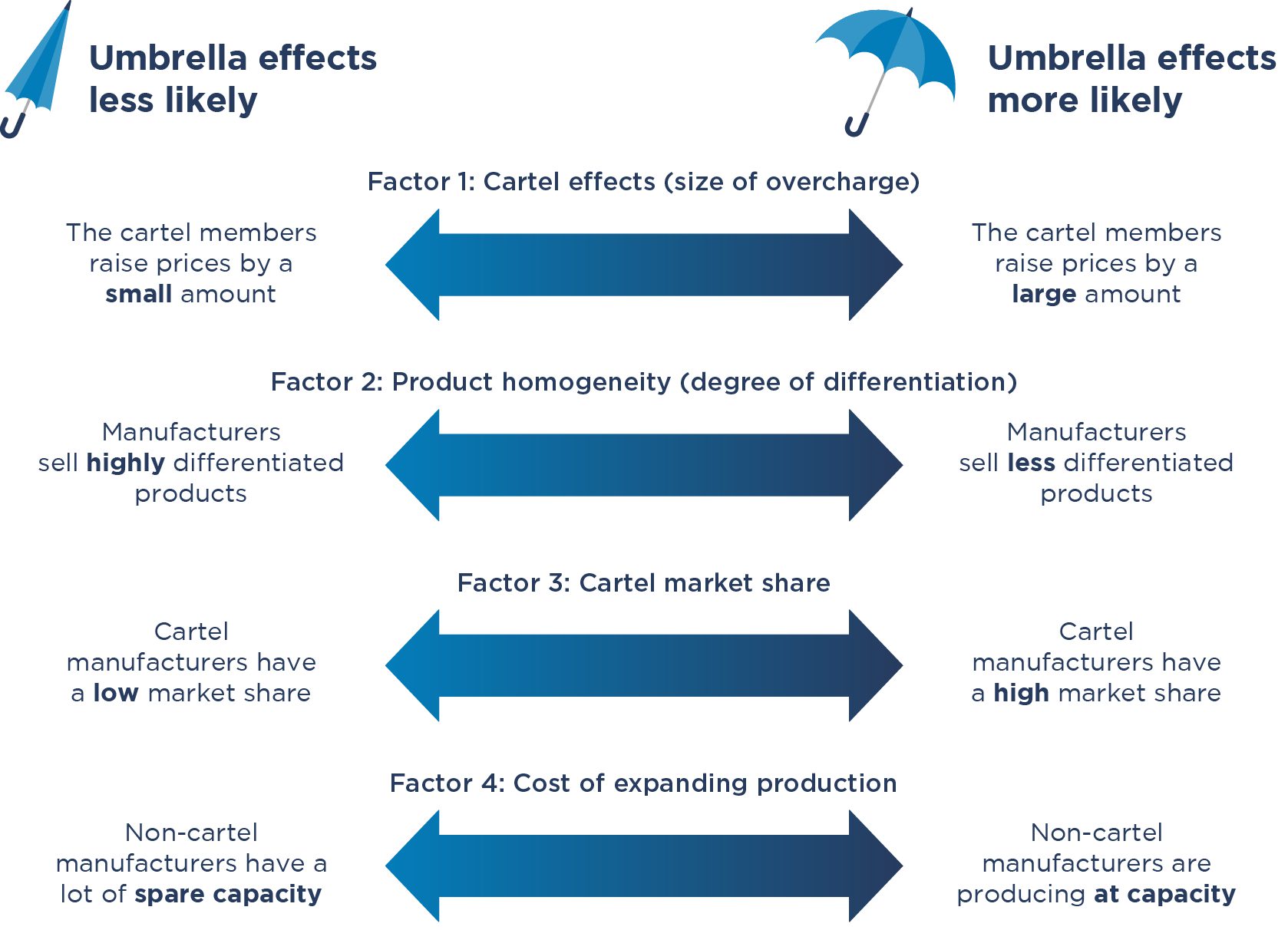

Economic theory identifies several factors that increase the likelihood and magnitude of umbrella effects:

a. High cartel effects: the higher the effect the cartel has on prices the higher the protective umbrella that non-cartelists enjoy, making umbrella effects more likely.

b. Homogeneous products: When products are highly homogeneous, non-cartel firms are more likely to raise prices in response to the cartel. In the extreme case of perfectly homogeneous products, non-cartel members could increase prices to the same level as the cartel. The more differentiated the products, the less demand diverted to non-cartel firms, hence limiting their reactions and the umbrella effects. Umbrella effects could also arise outside of the relevant market – products in adjacent markets may become substitutes if cartel markups are sufficiently high such that they drive customers outside of what we would typically define as the relevant market. [18]

c. High cartel market coverage: A cartel controlling a larger share of the market leaves fewer competitors outside the cartel. These remaining firms experience higher demand, making larger price increases more likely.

d. High costs for expanding production: When non-cartel firms face high costs for expanding production, they are less able to facilitate the increased demand. This constraint amplifies umbrella effects, as firms are more inclined to raise prices than to expand output. [19]

Take the previous example: Figure 1 below shows the conditions in which umbrella effects are more and less likely. Umbrella effects might be expected if the cartel members raise prices by a large amount, the manufacturers all sell similar products, if all but one firm are cartel members, and if non-cartel firms are producing at capacity.

Figure 1: The four factors affecting the likelihood and magnitude of umbrella effects

Predictions about the likelihood of umbrella effects can be validated using simple analyses. An upward pricing pressure analysis for non-cartel members for instance, can be used to assess whether a cartel’s higher prices create incentives for outsiders to raise their own. [20] The results of any analyses should however be considered alongside the broader case context. In reality, non-cartel members may face barriers to changing prices, such as contractual pricing agreements or limited bargaining power to negotiate price increases, hence limiting any potential umbrella effects. [21] Any findings should therefore be interpreted with attention to the wider economic environment.

Quantifying umbrella effects

If preliminary assessments suggest that umbrella effects may exist, the next step is to quantify them. Measuring the losses from umbrella pricing follows the same principles as estimating harm to the direct cartel customers. The core objective remains: to determine what is likely to have happened in the hypothetical “counterfactual scenario” where the cartel’s infringement did not take place.

The European Commission’s Practical Guide on Quantifying Harm in Actions for Damages (2013) (“Practical Guide”) [22] reinforces this idea, noting that the same techniques used to quantify harm to direct customers can also apply to indirect customers, including umbrella customers. [23]

The techniques set out in the Practical Guide – such as comparator-based methods, regression analysis, difference-in-difference, and simulation methods – are equally relevant for estimating the counterfactual prices charged by non-cartel firms in the absence of umbrella effects. Simulation methods are particularly comparable, as they rely on predicting the actions of firms outside the cartel.

Quantifying umbrella effects therefore requires the same methods as quantifying harm to direct cartel customers, and should therefore be treated the same. This alignment in core principles underlines the fact that the challenges in proving and quantifying umbrella effects need not lie with the practical tools available to us, but with the ability of national courts to use and accept such evidence.

Key takeaways

Umbrella effects are often overlooked in assessing cartel damages but are essential for fully upholding the objectives of the Damages Directive: compensating individuals for the full scale of harm caused by competition law infringements. Evaluating the true scale of harm requires considering these indirect effects, even if they go beyond the direct actions of cartel members.

Courts remain hesitant to accept umbrella effects. Proving causation and foreseeability is challenging, as the actions of non-cartel firms might appear too remote and influenced by factors unrelated to the cartel. These difficulties, combined with ambiguous legal frameworks, make the issue contentious in competition litigation cases. However, dismissing umbrella effects outright is unjustified. With advances in econometric techniques, causality assessments are strengthened and the same tools used to estimate harm for direct customers apply here. When based on reliable data, estimates of umbrella damages can serve as solid evidence for courts to rely upon.

As tools for assessing umbrella effects evolve, so too should the courts’ willingness to engage in the discussion. The issue is neither more complex nor less relevant than other dimensions of competition litigation, like overcharge or pass-on. Addressing umbrella effects will be a step towards complete understanding of the economic harm caused by anticompetitive practices.

References

-

Tara Ghobadian is an Economist, Patricia Lorenzo is a Senior Vice President and Bernardo Sarmento is a Vice President at Compass Lexecon. The authors thank the Compass Lexecon EMEA Research Team for their comments. The views expressed in this article are the views of the authors only and do not necessarily represent the views of Compass Lexecon, its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, its employees, or its clients.

-

Advocate General Kokott. (2014). Opinion in Case C-557/12, Kone AG and Others v. ÖBB-Infrastruktur AG, ECLI:EU:C:2014:45 (p. 1).

-

For simplicity, we refer to cartels throughout this article. However, umbrella effects may also arise in cases of information exchange or other forms of coordinated behaviour that do not constitute explicit price fixing agreements.

-

Umbrella effects could arise following any type of anticompetitive conduct, not just price fixing. In the case of purchasing cartels, for example, umbrella effects would be observed by way of lower prices for non-cartel members as well as cartel members.

-

Practical Guide Quantifying Harm in Actions for Damages based on breaches of Article 101 or 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (p. 41)

-

Practical Guide Quantifying Harm in Actions for Damages based on breaches of Article 101 or 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (p. 41).

-

Directive 2014/104/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 November 2014 on certain rules governing actions for damages under national law for infringements of the competition law provisions of the Member States and of the European Union Text with EEA relevance.

-

Court of Justice of the European Union. (2014). Judgment in Case C-557/12, Kone AG and Others v. ÖBB-Infrastruktur AG, ECLI:EU:C:2014:1317 (p. 6).

-

Advocate General Kokott. (2014). Opinion in Case C-557/12, Kone AG and Others v. ÖBB-Infrastruktur AG, ECLI:EU:C:2014:45 (p. 4).

-

Federal Court of Justice (Germany). (2020). Judgment of 19 May 2020, Case KZR 8/18.

-

Franck, J.-U. (2015). Umbrella pricing and cartel damages under EU competition law. EUI Working Paper LAW 2015/18 (p. 1).

-

Cour d'Appel de Paris. (2021). Arrêt du 24 novembre 2021, Pôle 5 - Chambre 4, RG 20/04265, N° Portalis 35L7-V-B7E-CBSQX (p. 17).

-

The court in the In re Vitamins Antitrust Litigation rejected umbrella claims citing difficulty to prove injury and calculate damages. The court in Costco Wholesale Corp v AU Optronics Corp in contrast recognised the standing of umbrella plaintiffs, noting that Costco would have to present evidence showing that higher prices were caused by the conspiracy. See Vitamin Antitrust Litigation, 2001 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 12114, at *20 (D.D.C. 2001) and Costco Wholesale Corporation v. AU Optronics, US District Court, Western District of Washington at Seattle.

-

Blair, R. D., & Durrance, C. P. (2018). Umbrella damages: Toward a coherent antitrust policy. Contemporary Economic Policy, 36(2), 241–254

-

Advocate General Kokott. (2014). Opinion in Case C-557/12, Kone AG and Others v. ÖBB-Infrastruktur AG, ECLI:EU:C:2014:45 (p. 9).

-

Franck, J.-U. (2015). Umbrella pricing and cartel damages under EU competition law. EUI Working Paper LAW 2015/18 (p. 1).

-

Inderst, R., Maier-Rigaud, F. P., & Schwalbe, U. (2014). Umbrella effects. Journal of Competition Law and Economics, 10(3), 742.

-

Inderst, R., Maier-Rigaud, F. P., & Schwalbe, U. (2014). Umbrella effects. Journal of Competition Law and Economics, 10(3), 755.

-

Inderst, R., Maier-Rigaud, F. P., & Schwalbe, U. (2014). Umbrella effects. Journal of Competition Law and Economics, 10(3), 746.

-

Other simple methods to validate predictions about the likelihood of umbrella effects could include comparing price evolution for cartel versus non-cartel firms; assessing consumer substitution patterns, by calculating cross-price elasticities and diversion ratios; and comparing average prices before and after the infringement for cartel and non-cartel firms.

-

Savio, M. B. (2020) Assessing Umbrella Pricing Incentives. Antitrust, Vol. 35, 88.

-

Practical Guide Quantifying Harm in Actions for Damages based on breaches of Article 101 or 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

-

Practical Guide Quantifying Harm in Actions for Damages based on breaches of Article 101 or 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (p. 41).