On the plausibility of small cartel overcharges

Share

In cartel cases, courts can dismiss small overcharges as inherently implausible. In this article, Jorge Padilla, Enrique Andreu, Salvatore Piccolo and Ben Dubowitz [1] assess this rule of thumb and show that it is not supported by the available empirical evidence. They present two reasons why a smaller overcharge may be the rational response for cartelists and argue that the debate should be reframed from whether small overcharges are plausible, to understanding when they occur and why.

View the PDF version of this article.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the authors only and do not necessarily represent the views of Compass Lexecon, its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, its employees or its clients.

Introduction

In cartel damages cases, the defendant often presents evidence that its overcharge was small. That estimate can be met with scepticism. However, no consensus exists on the circumstances when small overcharges should be considered plausible – or, even whether they should ever be considered plausible. Economists have developed increasingly sophisticated techniques to estimate damages, and regulators have issued guidelines setting out best practice.[2] But, the point at which an estimated overcharge becomes implausibly low remains unclear.

Nonetheless, courts need to make a decision. In our experience as expert witnesses, they often respond to this lack of clarity with a rule of thumb: that small overcharges are inherently implausible. Their reasoning is that firms are unlikely to risk the cost of detection – in fines and damages – unless the overcharge provides adequate incentive for them to do so, especially in long-lasting cartels.[3] However, small overcharges are an observable fact with an explicable rationale. The question should not be whether small overcharges are plausible at all. It should be: how common are they; and in what circumstances should we expect them to occur?

In this article, we look at the empirical evidence available on the prevalence of small overcharges, and describe two of the main reasons where cartelists would find it advantageous to set a small overcharge rather than a larger one. In both cases, a small overcharge serves a common aim: it stabilises the cartel. That increases the prospect of continuing to earn lower but more sustainable overcharges, and reduces the risk of detection that exposes all past overcharges to damages claims.

The empirical evidence on small overcharges

The natural starting point when considering the plausibility of small overcharges is to consider how frequently we observe them as a matter of fact. A common method for exploring this issue is a meta-study, which aggregates the findings from individual studies to provide a systematic overview. Perhaps the best-known example on cartel overcharges is research by Connor which is now in its fourth edition and is often cited in the economic literature and by authorities.[4]

In the most recent edition of the study, Connor (2024) found that the median historical overcharge is 25%. That estimate covers 709 price-fixing cartels throughout history – more than 60% of which operated since 1990.[5] In the most recent period, from 2000-2019, the median overcharge was 21%. That estimate is more relevant for our purposes and, although it is lower, remains in the same region.

This estimated median has come in for some criticism, [6] but it is likely a reasonable guide. In a study for the European Commission, Komninos et al. (2011) reviewed and cleaned the Connor datasets, removing some of the less credible data points, finding a median overcharge of 18%.[7] Other authors have used various econometric techniques for removing biases and found medians of 16%-18%.[8]

The more important criticism is that the median historical overcharge is only a very limited guide when assessing the plausibility of a small overcharge in a specific case. It merely states that, agnostic to circumstances, half of overcharges in the period between 2000 and 2019 were higher than 21% and half were lower.

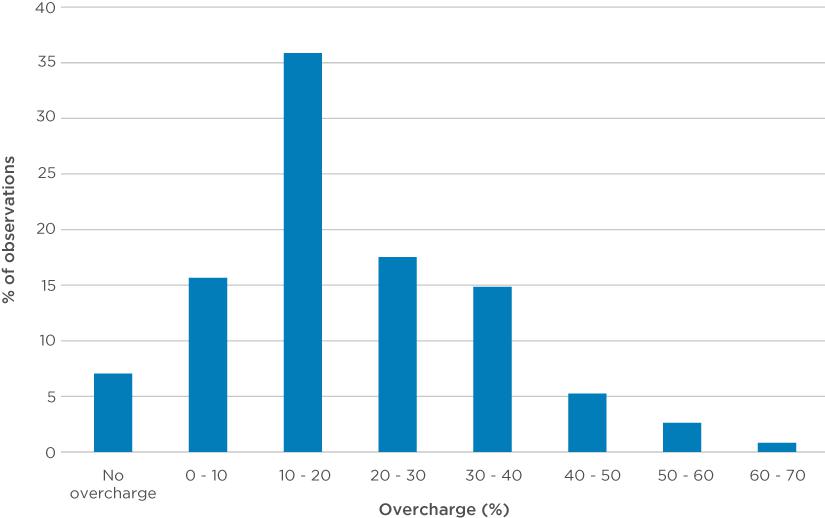

To better assess the plausibility of a small overcharge, we need a more detailed picture of how common small overcharges are in the cartels the study observes. Figure 1 below sets out the distribution of overcharges in the meta-study identified by Komninos et al. (2011) as reliable. Over the entire time period analysed:

- Half of cartels set an overcharge below 18% (i.e., the median);

- The most common range of overcharge was 10-20%;

- More than 1 in 5 cartels (23%) set an overcharge below 10%; and

- Around 1 in 15 (7%) achieved no overcharge– or rather, the overcharge was so small that the estimate is indistinguishable from it having no effect.

Already, this empirical evidence is much more useful than the median overcharge to any court that must assess the plausibility of a small overcharge. It shows that, before we consider any circumstances of the case at all, small overcharges are uncommon, but not vanishingly rare and certainly not inherently implausible. Of all observed cartels in history, 23% of them set overcharges below 10%.

However, prevalence is still a limited guide. The distribution also shows that some cartels had high overcharges: approximately the same number had overcharges in the range of 10-20% as 30-40%. There are clearly a wide-range of plausible overcharges, and it should be estimated on a case-by-case basis. The question, therefore, is not whether small overcharges can happen. They do. The question is: in what circumstances do they happen and why? For that explanation, we need to turn to economic theory.

Figure 1: Distribution of historical overcharges

The first explanation of when cartelists will prefer a small overcharge: it makes the cartel more stable, reducing the risk of disruption

The difference we observe between cartels with small overcharges and large overcharges is not random. Further, the reason is not simply that more than 1 in 5 cartels are bad at price fixing. A sensible starting point is that each cartel, including those observed in the meta study, sets the overcharge that it believes would maximise its total earnings. In this section, we explore the first reason that explains the set of circumstances in which a small overcharge would be more profitable for the cartel than a larger one.

Understanding the benefit and threat of disrupting the cartel

Once a cartel forms, each cartelist must consider its expected earnings in three future scenarios:

- The cartel remains stable. In this scenario, each cartelist continues to benefit from the overcharge into the future.

- The cartelist destabilises the cartel. In this scenario, all cartelists lose the prospect of continuing to earn the overcharge, but the cartelist that deviates from the cartel first may gain a greater benefit. For instance, a deviant can break from the cartel by setting a lower price than its overcharging rivals to gain market share, or by applying for leniency to avoid the fines that its competitors and former co-conspirators will incur.

- The cartel destabilises for other reasons. In this scenario, all cartelists lose the benefit of the overcharge. Here, however, the relevant cartelist gains no other advantage.

The crucial point here is that all cartelists benefit if the cartel remains stable. However, if the cartel collapses, each risks being worse off. At most only one of the cartelists can benefit from collapsing the cartel; the others are all worse off. The cartel only remains stable so long as each cartel considers that the net benefits of staying in the cartel outweigh the net benefits of destabilising it.

The centre of that consideration depends on how much each cartelist values, in present terms, the prospect of earning money in the future. In the economic and accounting jargon, this is referred to as the “time value of money”. It simply means that when a company stands to earn $100 million in a year’s time, the present value of that money is worth less than receiving $100 million today. A company’s patience to receive future earnings is represented by a discount factor between 0 and 1: the more patient a company is, the higher the discount factor.[9]

It is important to stress that the time value of money reflects much more than a company’s cost of capital. Rather, it measures how a firm weighs the prospect of near-term profits against the prospect of long-term profits, serving as a proxy for its patience. We discuss the specific circumstances that may affect a cartelist’s patience in the next section.

For each cartelist, the benefit of staying in the cartel compared with disrupting it depends on both:

- The size of the overcharge, which affects the benefits of both (1) remaining in the cartel; and (2) disrupting the cartel – as the gap between the overcharge and competitive rate increases, meaning a cartelist can potentially capture more market share; and

- Each cartelist’s patience, which determines the present value of remaining in the cartel or disrupting it.

As the nominal benefits of remaining in the cartel are more spread out over time than the nominal benefits of disruption, the present value of remaining in the cartel will not necessarily exceed the present value of disrupting it, even when the nominal value is greater. It depends on how aggressively each cartelist discounts the future earnings.

This interaction is fundamental for understanding when a cartel might benefit from setting a small overcharge. With patient cartelists, the cartel remains stable with a high overcharge, as all members of the cartel emphasise future earnings and place relatively less weight on short-term gains from deviating.

In contrast, the agreement between impatient cartelists is less stable with a high overcharge, and more stable with a low one. That is because the present value of disruption is more sensitive to the level of the overcharge than the present value of remaining in the cartel. That changes how the cartelists assess the trade-off between the two. As the overcharge increases:

- The nominal benefits from remaining in the cartel increase just as they do for patient cartelists, but here the impact on the present value is more limited as these cartelists heavily discount future earnings; and

- The nominal benefits from disrupting the cartel also increase, and because these benefits are relatively more short-term, they are less exposed to discounting, so the present value of disruption increases to a greater extent.

Ultimately, impatient cartelists do not value the long-term rewards as highly as they value near-term gains, and so a high overcharge merely incentivises each party to deviate and collapse the cartel.[10] So, to stabilise the cartel, the overcharge must be low enough that the present value of remaining in the cartel exceeds the present value of disruption. By agreeing to a lower overcharge, each cartelist reduces its exposure to the risk that one of the other cartelists deviates.

As a result, when cartelists are in circumstances that make them less patient, such that they have low discount factors, we should expect to observe that they set small overcharges. That reduces the returns provided by the overcharge, but it makes those returns more sustainable.

What circumstances affect a cartelist’s discount factor?

Having established the importance of the cartelists’ time value of money (the prospect of long-term gains against near-term profit), we now consider the factors that determine it. We should find small overcharges more plausible if the relevant party had circumstances that suggest it had a low discount factor (i.e., more impatient), and less plausible if its circumstances suggest it would have had a high discount factor (i.e., more patient).

Cartelists may prioritise present profits over future profits for several reasons:

- High cost of capital: When the cost of capital is high, future profits lose significant value compared to current profits, making cartelists more impatient.

- High probability of cartel breakdown:

- Regulatory factors: A greater likelihood of detection, fines or damages increases the tendency to discount future profits; and

- Economic factors: Market changes, such as mergers, new entrants, demand fluctuations or technological shifts, heighten the risk of collapse, making cartelists less willing to rely on long-term benefits. For instance, collusion is more likely to break down during demand booms, when the potential gains from increasing output are higher.[11]

- Slow detection of deviations: If cartelists cannot quickly identify deviations, a defector can profit from undercutting the collusive price for a longer period before triggering a price war. This delay increases the immediate benefits of deviation.

- Uncertainty about deviations: When cartelists are unsure whether a price drop stems from undercutting or external factors (e.g., weaker demand), they may hesitate to retaliate, reducing the cost of deviation.[12]

Each of these characteristics makes a small overcharge more plausible in the sense that they provide evidence of reasons that would make it rational for a cartel to pursue a low overcharge rather than a high one.

The second explanation of when cartelists will prefer a small overcharge: it reduces the threat of follow-on damages

The first explanation considered how cartelists choose an overcharge to maximise their expected future earnings. However, the threat of disruption to future earnings is not the only one cartelists must consider. The threat of collapsing the cartel brings two further costs:

- Fines, which are intended to disincentivise cartelists and are capped as a proportion of global turnover in the EU; and

- Follow-on damages, which allow wronged parties to receive damages equivalent to the harm the overcharge imposed on them.

In this section, we focus on the threat that follow-on damages pose to cartelists, and how they can manage that risk by further reducing overcharges to lower the probability of the cartel destabilising.

When a cartel sets the overcharge it considers not only the incremental benefit it expects from future earnings; it also considers the incremental risk that follow-on damages expose its past earnings to. At the start of a cartel’s life, this assessment is straightforward. There are no past overcharges at stake. The overcharge will be determined purely by the considerations we set out above to maximise expected profit. However, as time passes, the size of overcharges in past periods accumulates, all of which are subject to follow-on damages if the cartel is detected.

The level of overcharge affects the risk of disruption and detection; therefore, the threat to the cartelists’ past earnings may outweigh the potential benefit that future earnings from a given level of overcharge would provide. In the most extreme example (which is not likely, but is illustrative), the cartelists may have so much at stake from years of overcharges, that they would decide to “bank their winnings” – forgoing future benefits, as they are no longer worth the risk given the amount of overcharge accrued over the cartel’s lifetime. In this scenario, the cartel ceases and the overcharge effectively collapses to zero.

In practice, that situation is unlikely to occur. There will likely be some level of overcharge that makes the prospect of increasing future earnings worth the risk that cartelists expose their past earnings to – particularly as they will be unable to reduce the risk of follow-on damages to zero. However, reducing the overcharge does reduce the risk of disruption for the reason explained above. On that basis, whatever the level of overcharge the cartel would set to deter disruption before considering its exposure to follow-on damages, it would further reduce that overcharge when taking that risk into account.[13]

Where possible, a rational cartel that could regularly revise the level of the overcharge would decrease it over time to manage the increasing threat that follow-on damages pose. The longer the cartel operates, the higher the potential damages, the greater the downside to being caught without any corresponding increased upside. This incentivises caution on the part of cartelists through lower overcharges, thereby disincentivising costly disruption from fellow cartelists. An analogy is pension planning: early on investors are advised to put more money into stocks as their exposure to downside risks is less than the potential upside benefits; however, as they get closer to retirement, they are more exposed to the downside risks and the marginal benefit of further upside reduces, so they adjust to more cautious investments.

In a forthcoming paper, we find that private litigation is unlikely to ever totally remove cartels.[14] On the one hand, the possibility of private enforcement reduces the expected profitability of collusion; on the other hand, the reduction in the overcharge helps to preserve the stability of the cartel. We find that the latter effect often dominates, meaning we get more collusion but with lower overcharges.

Are small overcharges becoming more plausible?

We have shown so far that small overcharges do occur, and explained the circumstances in which a cartel would rationally prefer a smaller overcharge. At face value, the meta-study cited above shows that 22% of all cartels have set overcharges below 10%. We might therefore conclude that reveals the proportion of current cartels that are incentivised to have a small overcharge. However, that might not be the case. Recent policy developments have affected the stability of cartels, and therefore the overcharges that rational cartelists would set to manage those risks.

In this section, we consider recent developments that are likely to have increased the likelihood of small overcharges compared to their historical prevalence. What follows is by its nature speculative: although Connor (2024) shows that median overcharges between 2000 and 2019 are lower than the historical rate, the study does not state how the prevalence of small overcharges has changed in that period.[15] However, there is reason to believe that recent policy changes have made cartels more cautious and impatient. This is a compliment to regulators everywhere: as cartel detection improves and incentives shift against cartelists, we should expect that they manage that risk by reducing overcharges so as to buttress their stability.

Leniency programmes

First introduced in the US in 1993 and the European Commission in 1996 (and heavily revised in 2006), leniency programmes grant immunity or fine reductions to the first cartel member to apply for leniency.[16] These programs now underpin antitrust enforcement, with over half of all fines issued by the EC since 1998 including a leniency reduction, reaching over 90% in some years.[17]

By creating a "race to the door", leniency programs directly affect discount rates and incentives. Cartelists, fearing rivals will seek leniency first, are incentivised to deviate earlier, increasing impatience and reducing discount rates. A number of academic studies have confirmed the destabilising effects this has had on cartel formation, leading to the breakdown of previously stable cartels.[18]

It is therefore plausible that leniency has reduced long-term cartel stability, which has in turn reduced cartelist patience for long-term revenues. Based on our discussion above, we would expect that cartelists require lower overcharges to maintain their stability in periods and jurisdictions with leniency programmes than they require in periods and jurisdictions without it.

Settlement programme

Another policy that may have affected cartel discount rates is the introduction of the settlement process in 2008.[19] Under this programme, the EC offers detected cartelists the opportunity to cut short the lengthy legal process by acknowledging involvement and liability in return for a 10% reduction in their final fine.

The raison d’être of the settlement programme was to free up resources to tackle more cartel cases and widen the net of enforcement.[20] Similarly to the leniency programme, as cartelists face an increased threat of detection, our framework suggests cartelists should have become more impatient and overcharges would drop. However, this should be weighed against the stabilising impact of lower fines, and further investigation is needed before any conclusions are reached.

Damages Directive

The final policy that may have affected cartel overcharges is the EC’s Damages Directive, which came into force from 2014.[21] This set out the rules of engagement for follow-on damage claims, and ensured anyone who has suffered harm caused by a competition law infringement could effectively exercise the right to claim full compensation for that harm.

We have set out above the impact that the threat of follow-on damages has on cartel overcharges. Therefore, any cartel caught after 2014 would plausibly be expected to have lower overcharges than cartels in the same situation, all else equal, would have set before 2014.

The last two decades have seen policies intended to make life harder for cartelists, improve detection rates and increase follow-on damages. Each of these is likely to have the ultimate impact of making cartels more risk averse and place less weight on overcharges far into the future.

Conclusion

In this paper we have argued against the rule of thumb that small overcharges are inherently implausible. They are not. Cartels with small overcharges are historically uncommon, but not rare. Further, they occur for rational reasons. Reducing the overcharge mitigates the risk and threat of disruption to the cartel, reducing its potential earnings in principle but increasing the prospect of sustaining that lower overcharge in practice. That does not mean that collusion has become less feasible. Rather, it means that it continues with lower overcharges as cartels attempt to manage the threat of detection and disruption.

Going forward, we expect to see more small overcharges as rational cartelists seek to avoid increasing risk and cost of detection. Yet, to be clear, this does not mean that we should not worry about small overcharges; even small overcharges can cause great social harm, especially for products that are consumed in great quantities. Neither does it mean that we should not continue enforcing our cartel laws vigorously. On the contrary, the threat of cartel laws and their enforcement plays a crucial role: it increases the incentives for cartelists to reduce their overcharges to avoid detection, whether they are later detected or not.

View the PDF version of this article.

References

-

Jorge Padilla is Chair of EMEA Practice, Enrique Andreu is an Executive Vice President, Salvatore Piccolo is a Vice President, and Ben Dubowitz is an Economist at Compass Lexecon. The article is based on a forthcoming paper (see here). The authors thank Jasper Haller, Soledad Pereiras, and the Compass Lexecon EMEA Research Team for their comments. The views expressed in this article are the views of the authors only and do not necessarily represent the views of Compass Lexecon, its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, its employees or its clients.

-

European Commission, Communication from the Commission on quantifying harm in actions for damages based on breaches of Article 101 or 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union Text with EEA relevance.

-

See for instance, KRB 2/05 – Berliner Transportbeton I, paragraph II.2.b.aa.

-

Connor, J. M. (2024) Price-Fixing Overcharges: Revised 4th Edition. Neelie Kroes, “Private and Public Enforcement of EU Competition Law – 5 Years On,” speech before the International Bar Association (March 12, 2009). See here.

-

Ibid.

-

For instance: critics such as Cohen and Scheffman (1989) assert that a 10% overcharge may be too high, especially in cases that relate to high-volume commerce, where price increases would likely reduce sales; Adler and Laing (1997, 1999) consider US fines excessive or punitive; and For example, Allain et al. (2011, 2015) found that fines imposed by the European Commission fines often exceed the optimal amount and, therefore, the likely overcharge. Cohen, M. A., & Scheffman, D. T. (1989). The antitrust sentencing guideline: Is the punishment worth the costs. Am. Crim. L. Rev., 27, 331. Adler, H., & Laing, D. (1997). Application of US Antitrust Laws to mergers and joint Ventures in a Global Economy (2). European Business Law Review, 8(4). Adler, H., & Laing, D. J. (1999). As corporate fines skyrocket. Business Crimes Bulletin, 6(1).

-

Komninos, Assimakis, et al. "Quantifying antitrust damages: Towards non-binding guidance for courts." (2010).

-

Boyer, Marcel and Kotchoni, Rachidi, (2015), How Much Do Cartel Overcharge?, Review of Industrial Organization, 47, issue 2, p. 119-153; Smuda, Florian, (2014), Cartel overcharges and the deterrent effect of EU Competition law, Journal of Competition Law and Economics, 10, issue 1, p. 63-86.

-

Which is one minus the rate at which it discounts future earnings by: a cartelist that discounts the future significantly is more impatient and will have a higher discount factor.

-

It also follows from the theory above that small overcharges are plausible when, for a given cartelists’ discount factor, the critical discount factor is relatively high, irrespective of the size of the overcharge. One of the reasons why that may be the case is that cartelists find it difficult to coordinate a price war effectively once a deviation has been discovered. If they are not able to agree to launch a price war because, each firm prefers the others to punish the deviant by setting low prices, then the critical discount factor will be high. And when that critical discount factor is high, collusion is only viable if the overcharge is small.

-

Rotemberg, J. J., & Saloner, G. (1986). A supergame-theoretic model of price wars during booms. The American economic review, 76(3), 390-407.

-

Green, E. J., & Porter, R. H. (1984). Noncooperative collusion under imperfect price information. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 87-100.

-

The cartel overcharge will be smaller when: The probability of detection and the scope of the damages’ claims is larger; cartel members hold a larger share of the market and therefore face greater potential damages; and/or the cartel has existed for a long time because the longer the cartel operates, the higher the potential damages, encouraging cartel members to moderate overcharges as detection becomes more costly.

-

Andreu, E., Padilla, J. & Piccolo, S (2024). “Collusion with Anticipated Damages Claims”, Forthcoming. See here.

-

The median is 21% for the period 2000 – 2019 and 24% for the period 1990 – 1999.

-

European Commission (2006) Commission Notice on Immunity from fines and reduction of fines in cartel cases

-

Marvão, C., Spagnolo, G. Leniency Inflation, Cartel Damages, and Criminalization. Rev Ind Organ 63, 155–186 (2023). See here. Given an average of five firms per cartel, this translates into around three members per cartel that obtain leniency.

-

E.g., Miller (2009) Strategic Leniency and Cartel Enforcement; Zhou (2016) Evaluating Leniency with Missing Information on Undetected Cartels: Exploring Time-Varying Policy Impacts on Cartel Duration

-

Commission Regulation (EC) No 622/2008 of 30 June 2008 amending Regulation (EC) No 773/2004

-

Antitrust: Commission introduces settlement procedure for cartels – frequently asked questions: “This should free resources to deal with other cases, increasing the detection rate and overall efficiency of the Commission’s antitrust enforcement. This is also expected to have a positive impact on general deterrence”. See here.

-

Directive 2014/104/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 November 2014 on certain rules governing actions for damages under national law for infringements of the competition law provisions of the Member States and of the European Union Text with EEA relevance.