Connected TVs: Will they follow the same path as mobile ecosystems?

Share

A connected TV is a larger, more specialised tablet/smartphone. Ciara Kalmus [1] explores whether the market for connected TV operating systems might consolidate – as the market for smartphone operating systems did – and, if so, what issues that might raise for competition authorities, media regulators, and public services broadcasters.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the authors only and do not necessarily represent the views of Compass Lexecon, its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, its employees or its clients.

The final text of the European Digital Markets Act (‘DMA’) refers to connected TVs as a core platform service, meaning that they fall within the scope of the regulation, if a provider is designated as a gatekeeper.[2] Connected TV operating systems (‘OSs’) have obvious parallels with mobile phone OSs, but so far, the market is not very concentrated and there are few complaints of unfair practices.

In this paper, I consider whether the market for connected TV OSs is likely to follow a similar trajectory as for mobile OSs and the consequences that regulators may consider if it does. Key questions are whether the market might consolidate so that one or more operators may acquire market power and, if so, how that would affect the market for content providers. Although consolidation could lead competition authorities to raise issues similar to the ones they identified with respect to mobile OSs, it may also raise different issues, particularly for media regulation and public service broadcasters.

What are connected TVs?

Connected TVs are television sets that connect to the internet. They can be used as a conventional TV set to watch broadcast TV, but also to stream content, browse the internet and view photos. This content can be presented directly as individual programmes, or as apps on a home screen, allowing the user to choose from subscription (e.g., Apple TV, Crunchyroll, Disney +, Netflix, and Prime Video) or free (iPlayer, YouTube, All4) video on demand (VOD) services. Most also have a web browser, allowing viewing of more general internet content.

Each connected TV has an OS, which allows the TV to run apps and digital content. Initially, these OSs were provided by individual manufacturers and pay TV operators, but this is changing. Of the large TV manufacturers, only Samsung and LG continue to operate their own OSs. Sony, Panasonic and Toshiba have switched to Google’s Android OS (for TVs), which is available for free. Amazon also has a growing share of the market. Its Fire TV OS is available both pre-installed on televisions (e.g., by manufacturers such as JVC) and as a “Fire Stick”, which can be plugged in.[3]

How might the market for TV operating systems evolve?

The economic features of connected TV OSs

Connected TV OSs potentially meet most of the criteria for a “core platform service” under the DMA.[4] These features are also common with other core platform services such as mobile OSs.

-

- Connected TVs are a multi-sided market connecting business users (content providers and advertisers) with end users (viewers). There is a significant degree of dependence on both business and end users for the service.

- There are economies of scale. The costs of development are largely invariant to the number of users, and the trend for increasingly advanced features makes it difficult for smaller pay TV operators and manufacturers to maintain their own OS. Voice control and search features are now standard and are particularly demanding as they require cloud-based speech recognition and a content suggestion system. OSs also need an app store, requiring the manufacturer to either develop their own solution or outsource it to third parties. There must also be the ability for software updates to support new features and to support new apps that emerge over time and existing apps that are updated. This results in substantial ongoing development spend.

- TV OSs are characterised by indirect network effects. Each app needs to be customised to the platform, incurring development costs for both the content provider and the platform. App developers want to make apps for platforms with the largest number of users, and users want platforms where quality apps – including new ones – are available. App developers with limited resources may prioritise improving the quality of their apps on major OSs, rather than developing an app for an OS with a small share of viewers.

- There are significant synergies for existing large digital players, which reduces incremental development costs. For example, where a TV OS provider (such as Google or Amazon) has already developed a mobile OS (such as Google’s Android OS), voice-controlled devices (such as either companies’ brand of smart speakers) and virtual assistants (such as Google Assistant and Amazon’s Alexa), it reduces the barriers to entry and may facilitate entry by platform envelopment.[5] These same synergies can also result in significant efficiencies for end users, as connected TV users can benefit from using voice search technology already developed for mobile OSs and smart speakers.

- There are direct network effects which benefit companies that can combine data across multiple digital services. For instance, many connected TV OSs use data on a user and similar users’ characteristics and tastes to recommend content. The greater the number of users – both on the TV platform and other services owned by the TV OS provider – the better targeted the recommendations for all users.

These economic factors could potentially lead the market to consolidate. Furthermore, the synergies and network effects between digital markets could mean that the beneficiaries will be the same companies that already have leading positions in other markets.

However, in practice, there are still many different connected TV OS providers with different business models. At a global level, Mediatique estimated that Google’s Android and Samsung’s Tizen each accounted for a 23% OS market share, with Roku, the next largest at just 6%.[6] Shares in individual countries and regions can be more concentrated. In the UK, Mediatique estimated that Google’s Android system accounted for 33% of OSs in 2020, compared with 28% for Samsung’s Tizen.[7] In the United States, Roku is estimated to be the largest platform, installed on an estimated 38% of connected TVs.[8] The relative fragmentation of the market is in contrast to other core platform services which are already concentrated. If market shares stay unchanged, then it would be difficult to designate operators with gatekeeper status and thus subject to ex-ante regulation.

Potential parallels with the market for smartphone OSs

In considering how the market for connected TV OSs is likely to evolve, it is worth reviewing how the market for smartphone OSs developed, and the extent to which the two markets have parallels.

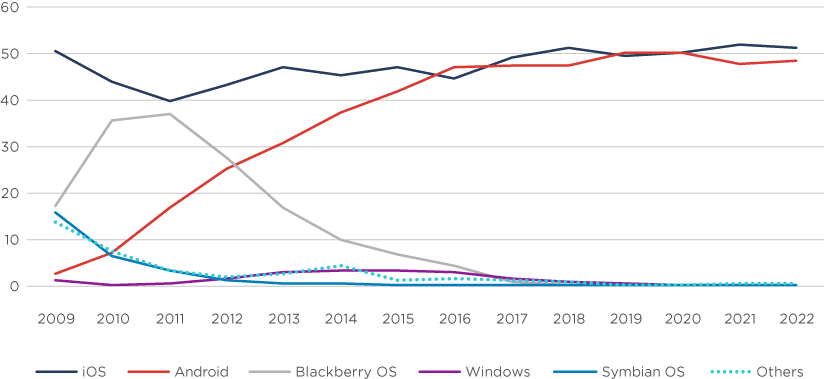

When smartphones first emerged in the period 2007-2012 there were a number of competing OSs – just as there are for connected TVs currently. The chart below, from the CMA Mobile Ecosystems Interim Report, shows that in 2009, smartphones offered a range of OSs including Nokia’s Symbian and BlackBerry. However, by 2015, virtually all smartphones used either Apple’s iOS or Google’s Android system.[9] In contrast to the rapid movement in the period 2009-2014, shares have remained virtually unchanged since 2015.

Figure 1: Market share of Mobile OSs in the UK, 2009-2022

On the one hand, the market for connected TVs might follow a similar trajectory, as the economic features of the OSs are similar to those of the OSs for smartphones: economies of scale, network effects, and synergies with other digital platforms. Both are platforms for content apps that connect viewers/end users with content providers/developers. Both platforms are also characterised by economies of scale and indirect network effects. Both are products where the overall quality for consumers depends on a combination of hardware and software, but it is relatively easy for specialist hardware manufacturers and specialist software developers to cooperate through licensing. Essentially, a connected TV can be considered as a larger, more specialised smartphone or tablet.

On the other hand, connected TV OSs exhibit some notable differences to mobile OSs – and to other core platform services – each of which could, to some extent, mitigate the economic forces that tend towards consolidation.

-

- Switching costs: Compared with mobile OSs, barriers to switching between OSs are lower for connected TVs. A consumer switching from an Apple to an Android phone may need to repurchase their apps, and risks losing some data. By contrast, for connected TVs, subscriptions to apps (e.g., Apple TV, Crunchyroll, Disney +, Netflix, and Prime Video) are normally independent of the OS. Consumers to date may not have had strong preferences for a particular TV OS.

- Multi-homing: In contrast to mobiles, where each device is constrained to one OS, viewers of connected TVs commonly have access to more than one OS. A viewer could have an LG TV (which uses its own OS), connected to a Sky Q box, with an Amazon Fire TV Stick plugged in. Users can toggle between the different systems so that if, say, the All 4 app is not available on the LG OS, viewers can still access it by toggling to Amazon Fire, or even AirPlay it from an iPhone.

- Bargaining power of content providers: Over a million mobile apps are available on Apple’s App Store and Google’s Play Store, whereas Google’s TV app store has only around 7,000 apps, of which only a handful might be considered “anchor content” – popular apps that that most consumers expect to be available.[10] The small number of providers producing “anchor content” may make it more viable for large manufacturers like Samsung and LG, and pay TV providers like Sky, to maintain their own OSs. It also means that key content providers have some bargaining power, as viewers expect their content to be available on their TV set.

Consolidation is not inevitable. It remains to be seen whether the factors above will militate for or against consolidation in this case. Ultimately, the issue may come down to the scale of development costs, and whether it remains valuable for TV manufacturers (or pay TV operators) to develop their own OSs when they are able to license one for free, or at least for no direct or upfront payment.[11] For example, Android TV’s Operator Tier allows TV operators to keep their brand on the user interface, while using Google’s underlying technology to access over 7,000 apps in the Google Play Store, use Google Assistant for searches, and interoperate with other Google smart home devices. In 2020, 160 companies – including Sony, SHARP and Panasonic as well as pay TV operators – used Android TV’s Operator Tier.[12] Faced with high and ongoing development costs of maintaining their own OS, the option to use a ready-made fully developed OS for free, which also offers efficiency benefits, might be hard to resist.

On that basis, it is useful to consider what the potential impact of consolidation in the connected TV market might be, as this may differ from other core platforms.

What impact might consolidation have?

Even if the TV OS market becomes more concentrated, there is a question as to whether it matters. Consolidation could create market power, which would be a concern if it results in consumer harm. In contrast, and potentially in combination, consumers may benefit if the market consolidates around an open standard and where consolidation is the result of the market offering a superior product with greater efficiencies. Whether or not the net effect is positive or harmful for consumers, consolidation would likely affect multiple markets in different ways.

The impact on the market for TV sets

A market that could be directly affected by market power in TV OSs is the supply of TVs. Just as smartphones largely replaced traditional mobile phones, connected TVs are replacing traditional TVs.

The impact on this market will, in part, depend on OS providers’ business models. In the short term, the provision of a high-quality OS, essentially for free, lowers prices and improves the quality of connected TVs, benefitting those who buy them. In the long term, the impact on consumers is potentially more complex, depending on many factors that affect competition within OS ecosystems (i.e., competition between rival manufacturers and content providers with access to the same OS) and between rival ecosystems based around different OSs. As seen in other industries, widely adopted OSs can act as a common standard and be highly beneficial both for technical progress and for competition.[13]

The impact on content markets

Connected TVs will likely affect the market for video content (i.e., TV channels, streaming services, and producers of content, including TV programmes) as OSs change how TV users interact with content and, importantly, which content has prominence. For example, the home screens, recommendations and search functions that OSs provide will affect which content viewers consume. Prominent TV content is more likely to attract viewers. On traditional broadcast TV, channels at the top of the Electronic Programme Guide (EPG) typically attracted larger audiences and were valued many times higher than those further down. A 2018 report for Ofcom on the UK market in EPG positions valued slots on the first page of the Sky EPG at an average of £22.5m each, more than double the value of slots on the third page.[14]

On a connected TV, a home page can display either content apps (such as Apple TV, iPlayer, Netflix, Prime Video, or YouTube) or individual programme recommendations from multiple service providers. This home page takes the place of the EPG as the route for content discovery, with more prominent content likely to attract more viewing. Relative to the fixed slots of the EPG, the home page of a connected TV allows more variety in terms of which content is shown, with the potential for the home page to be tailored to the individual viewer.

In the mobile industry, OSs’ influence on prominence led to the concern that, where the same company controls the OS and also provides content, it could self-preference its own content to the disadvantage of rival content providers. Certainly, if the market consolidates, then the opportunity to self-preference may emerge; both Google and Amazon already provide TV OSs and video streaming services – YouTube and Amazon Prime Video. However, whether any company would have the incentive to self-preference would need to be assessed in this specific context, as would the potential impact of such an approach. Although the immediate impact of giving prominence to one’s own content is obvious, it reduces the quality of service offered to consumers and so, the success of the strategy depends on a company’s ability to lock-in customers.

Another concern that emerged in the mobile industry was whether an OS with market power could impose supra-competitive charges (or other contractual terms) on content providers, for instance, when they take a share of subscriptions and in-app purchases.[15] Certainly, connected TV OSs have analogous opportunities. For instance, Amazon’s Fire system includes Amazon Channels where users can subscribe to streaming services such as Hayu (for reality TV series) directly through their Amazon account.[16] This is convenient for consumers, making it easy to sign up and allowing them to pick and choose which individual streaming services they subscribe to, rather than subscribing to pre-determined bundles. The content provided on Amazon Channels is subject to a commission, essentially turning the OS into an à la carte pay TV service.

However, to date, content providers have sufficient alternatives to mitigate concerns that OS providers would have power over them. Although Amazon offers content through Amazon Channels, viewers can also download apps and separately subscribe through websites without payment to Amazon. For instance, in the US, HBO had 5m subscribers through Amazon channels until it withdrew in September 2020, after which its content was only available as an app.[17] Even if the market consolidates, content providers may still be able to make their content available for download at no charge or benefit from multihoming, which would mitigate concerns over supra-competitive pricing.

The impact on advertising markets

After online advertising (£7.7bn in the UK in 2021), TV advertising is the second-largest advertising market, estimated to be worth £5.4bn in 2021, almost 25% above 2019 levels.[18] To date, TV advertising has been more resilient than press and other advertising in the face of online competition. Currently, most of this advertising revenue is on broadcast television, but as the share of viewing on VOD increases, it is inevitable that more will move to connected TVs. Research firm Sparkninety estimates that in the longer term, most broadcaster advertising will be addressable (i.e., targeted) advertising on connected TV platforms.[19]

Whether or not the market of OSs consolidates, connected TV will likely change the market for TV advertising, affecting both the revenue it generates and how it is distributed.

Connected TVs support targeted advertising. Automatic content recognition technology tracks which content is being watched on the TV and where it is sourced from. Depending on privacy rules, the user’s IP address can be collected and then matched and linked with other data associated with the user’s IP.[20] This data allows both targeted advertising on the smart TV device itself and better customer profiles which could be used to target data from other sources. This advertising can be either shown directly as display ads on the TV’s home screen (e.g., some Samsung TVs have “first screen” advertisements on the home page) or inserted into ad-funded VOD services such as YouTube or ITV Hub or even regular programming ad breaks (e.g., the UK ad-funded channels ITV and Channel 4 have targeted ads when viewed on the Sky platform).

The transition to targeted advertising does not depend on whether the market for TV OSs consolidates. On connected TVs, broadcasters and pay TV operators already use data on viewing behaviour to target advertising. For instance, Sky’s AdSmart technology allows advertisers to target viewing at particular demographics, and so a live broadcast shown over its SkyQ platform can show different advertisements to different viewers. ITV also offers a similar product, Planet V, for targeting viewers who use its streaming service. In principle, all parties should benefit from this transition: consumers should see more relevant adverts, advertisers should reach more relevant consumers, and content providers should earn more revenue.

Concern about consolidation could emerge if an OS gains sufficient market power to extract a supra-competitive proportion of content providers’ advertising revenue – this concern is analogous to the concern regarding subscriptions and in-app purchases discussed above. Some OS providers already charge carriage fees that take the form of sharing content providers’ advertising revenue or inventory. For instance, in the US, Roku’s standard terms require channels to adhere to its distribution policy. This requires that ad-supported apps make available a proportion of their total advertising inventory in the app to Roku. Amazon has adopted a similar advertising policy in the US only. This shows the potential for platform providers to extend from providing the OS to taking a share of the lucrative TV advertising market. If such terms came into effect in Europe, they could have significant implications for ad-funded broadcasters, such as Channel 4 and ITV, and their ability to fund the content needed to compete with streaming services.

What are the regulatory implications?

Unlike mobile OSs, connected TV potentially raises issues for both competition authorities and media regulators concerned with plurality.

Competition issues

If there is consolidation in connected TV OSs, the market may come to attract the attention of competition authorities in the same way that mobile ecosystems have done. As connected TVs are listed as a core platform service in the DMA, it is possible that one or more operators may be designated as a gatekeeper in future, and then subjected to the restrictions under the DMA.

To date, the competition risks of connected TVs in Europe are more theoretical than real. In particular, there are limited complaints of unfair practices, and there continue to exist a number of OSs – Samsung, LG, Amazon, Google and pay TV operators – without any one platform achieving market power.

It is possible that multiple OSs will continue to exist in the future. However, if the market does change, the rules for gatekeepers under the DMA would impose significant limitations if applied to connected TVs. Gatekeepers would face limits on their ability to set prices or other general access conditions.[21] They would also face restrictions on their ability to use data gathered from other services for connected TVs and would be required to share data with business users.[22] They would also be prohibited from self-preferencing, limiting the extent to which operators could favour their own content.[23]

Media regulation issues

The digital disruption of TV brings additional issues that did not arise with mobile OSs.

Broadcasting in Europe has traditionally featured a large role for state-funded public service broadcasters (‘PSBs’). These broadcasters were originally given state funding at a time when there was limited availability of broadcasting frequency, high entry costs and the inability to exclude non-payers. Although technological developments have since changed these factors, public service broadcasting has been maintained to achieve public policy objectives such as the promotion of accurate and impartial news and programmes of cultural significance which may be underprovided by the market.

Europe’s PSBs have typically occupied privileged positions at the top of the EPG, often with no payments attached. With connected TVs, there are no longer fixed slots for channels, and they may need to compete for space on the home screen with global streaming services such as Apple TV, Disney+, Netflix, Prime Video and YouTube. So far, in the UK, traditional broadcasters such as the BBC, ITV and Channel 4 have been able to secure prominent positions on connected TVs without having to pay for prominence or to give up advertising revenue.[24]

However, even if no gatekeepers emerge, OS providers can auction to the highest bidders the most prominent slots on the home page and in their recommendations. As negotiations often occur at a global level, national broadcasters can be at a particular disadvantage. Global content providers could agree preferential deals for prominence, which marginalise national broadcasters, even if their content is popular with (regional) audiences. Content may be recommended not based on what is of interest to the viewer (or has high public value) but on which content provider has paid the most.

Even if connected TV operators are designated as gatekeepers, Europe’s national broadcasters are likely to face a much tougher environment. These broadcasters have benefitted from favourable industrial policy, aimed at promoting public service broadcasting. Without the profits of Amazon, Apple, or Disney, they will struggle to obtain prominent positions for their content, without specific regulatory intervention. Although DMA rules may stop gatekeepers from self-preferencing, prominence could still be given on a financial basis, or negotiated globally in a way which favours global content providers, rather than national PSBs with more limited budgets. Although the Audiovisual and Media Services Directive (AVMS) requires content providers to give prominence to European Works on their service, it does not guarantee prominence for national PSBs on connected TVs.

Such prominence is proposed in the UK broadcasting white paper, published in April 2022. The government plans to introduce rules that would require PSB content to be available and prominent on connected TVs, streaming sticks and pay TV services. This proposed intervention is a significant industrial policy in favour of PSBs, motivated by public policy rather than competition concerns. There is no obvious parallel to this in the smartphone market.

The exact details of what such prominence may mean in a world where viewers find content through personalised recommendations is to be specified in Ofcom guidelines. These guidelines need to strike a balance between promoting PSB content and ensuring that viewers find the content that is mostly likely to interest them. Viewers who have paid to subscribe to services such as Apple TV, Disney+, Netflix, and Prime Video will expect to see that content displayed prominently on their screens and may be perturbed if there is excessive promotion of PSB content.

Such terms also have financial implications for platforms. The requirement to carry PSB services makes it unlikely that platforms will be able to extract carriage fees, such as a share of ad inventory (at least without benefits in return). In addition, the requirement to make prominent PSB content takes valuable space that could otherwise be sold to other content providers. Given what is at stake, such terms are likely to be highly contested.

Conclusion

The market for connected TV operating systems may or may not consolidate, but the underlying economics suggest that it might. If that means OS providers attain market power, then competition authorities may ask the same questions they have asked when assessing the impact of consolidation in the smartphone OS market. Regardless, the disruption that will follow connected TVs raises additional issues for media regulators, motivated by public policy as well as concerns about competition.

Read all the articles from the Analysis

The views expressed in this article are the views of the author only and do not necessarily represent the views of Compass Lexecon, its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, its employees or its clients.

[2] Recital 14 of the DMA names connected TVs as a core platform service.

[3] The Fire operating system uses the Android Open Source Project (AOSP) as a base. AOSP allows anyone to start with a basic version of Android before developing their own code. This is distinct from the Android TV operating system developed by Google. It does not support the Google Play Store nor any Google apps. Amazon Fire has a separate app stores, apps, interface and browser.

[4] DMA, recital 2.

[5] Eisenmann, T., Parker, G., and Van Alstyne, M. 2011. “Platform Envelopment.” Strategic Management Journal 32(12):1270–85.

[6] Mediatique, Connected TV Gateways: A report for Ofcom, p19 and p42.

[7] Mediatique, Connected TV Gateways: A report for Ofcom, p19 and p42.

[8] See https://9to5google.com/2021/05/03/roku-global-streaming-marketshare-drops/

[9] Statcounter, accessed on 25.03.2022.

[10] Why operators should migrate to Android TV, p7.

[11] Rethink Research, Android TV shifts to Google TV.

[12] Infomir, Why operators should migrate to Android TV, p4.

[13] Jorge Padilla, John Davies and Aleksandra Boutin, Economic Impact of Technology Standards (2017).

[14] Expert Media Partners, Report on the UK Market in EPG Positions (2018), p12

[15] For instance, Spotify complained to the European Commission about Apple’s App Store practices. See John Davies, Peter Bönisch, Rashid Muhamedrahimov, “Testing, Testing…” (2021).

[16] David Katzmaier, “Amazon Prime Video Channels: All the TV channels you can add to your Prime account”, CNET.com (2021).

[17] Karen Benardello, “WarnerMedia Removing HBO Subscriptions From Amazon Prime Channels” CinemadailyUS.com (2021).

[18] “£1 billion more invested in TV advertising in 2021”, Thinkbox.tv (2022).

[19] Sparkninety, Connected TV advertising dynamics, report for Ofcom, Nov 2020, slide 9.

[20] Trey Titone, “Automatic Content Recognition Explained”, Adtechexplained.com (2019(+).

[21] DMA, recital 62.

[22] DMA, Article 5.

[23] DMA, Article 6.

[24] Sparkninety, Connected TV advertising dynamics, report for Ofcom, Nov 2020, slide 23.