Retail mergers with supplier power

Share

Supplier power is a neglected element of merger assessment. Joe Perkins and Shiva Shekhar [1] illustrate how a supplier with brand power can effectively offset the impact of a downstream merger to protect its pre-merger profits and, as a consequence, protect consumers.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the authors only and do not necessarily represent the views of Compass Lexecon, its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, its employees or its clients.

There has long been recognition of the importance of buyer power when assessing potential impacts of a merger.[2] When the buyers of a product have lots of negotiating power, such as supermarkets buying from farms, this is likely to mitigate the effects of an upstream merger: an attempt by the merged supplier to raise its prices could be undermined by the strong bargaining position of the buyer.

Competition authorities incorporate this understanding of buyer power into their assessments of mergers. For instance, the European Commission’s 2004 merger guidelines state that “Even firms with very high market shares may not be in a position, post-merger, to significantly impede effective competition, in particular by acting to an appreciable extent independently of their customers, if the latter possess countervailing buyer power. Countervailing buyer power in this context should be understood as the bargaining strength that the buyer has vis-à-vis the seller in commercial negotiations due to its size, its commercial significance to the seller and its ability to switch to alternative suppliers.” When discussing coordinated effects of mergers, the Commission guidelines also note that “a large buyer may make coordination unstable by successfully tempting one of the coordinating firms to deviate in order to gain substantial new business.”[3]

In contrast, the importance of supplier power has been discussed much less in academic economics or competition policy discussions, despite its clear relevance to business decision-making in some industries. In particular, suppliers of branded consumer goods can have considerable influence over retail prices and can enjoy significant brand loyalty from consumers – such that some suppliers have more brand recognition than the retailers which sell their products. For instance, consumers of fashion or electronic devices may be very loyal to the companies that supply those goods, and largely indifferent about which retailer they buy them from. Indeed, supplier bargaining power is described as one of the key forces shaping business strategy in Michael Porter’s influential Five Forces model.[4]

In this article, we discuss how supplier power affects the impact of a downstream merger. Powerful suppliers have the incentive and ability to incorporate the expected effects of the merger into the wholesale prices they offer retailers.[5] In this way, a supplier can effectively offset the impact to protect its pre-merger profits and, as a consequence, the merger may have little or no effect on final consumer outcomes, such as prices and quality.

How supplier power can transform the impacts of downstream mergers

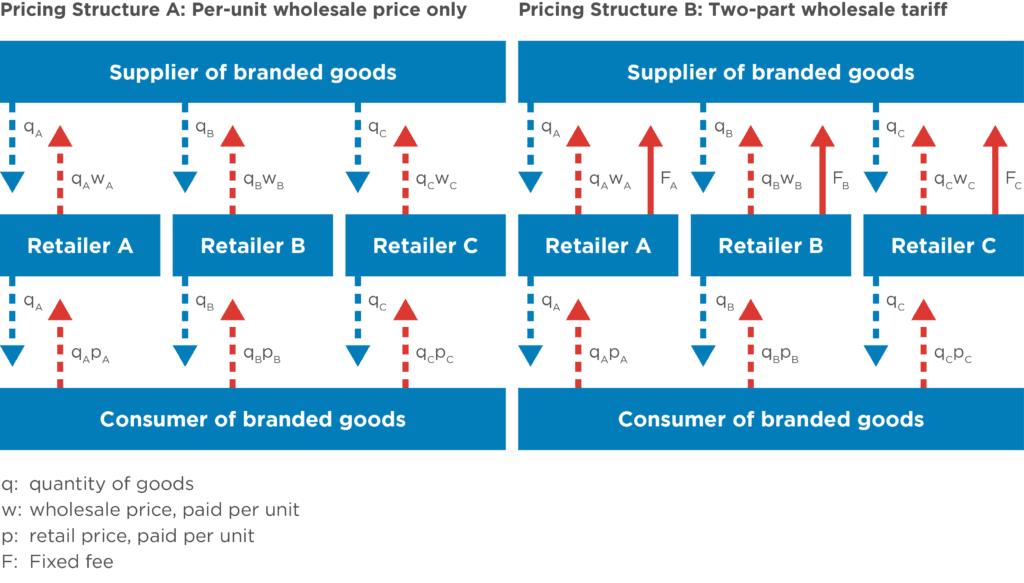

To understand the importance of supplier power, consider pricing incentives for a monopoly supplier and three retailers in a simple market structure like that depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Illustrative market structure for a branded good

The retailers compete with each other by setting prices for the supplier’s branded good, each taking into account the prices it expects the other retailers to set. The extent to which the retailers can differentiate from one another depends on the “retail experience” they offer. That may emerge simply from different physical locations of stores, or it could include other factors, but it does not include the product itself – i.e., whichever retailer a consumer chooses, they will purchase the same product.

In this setting, it is relatively straightforward to analyse the static price impacts of a merger between two of the retailers. For instance, the well-established GUPPI (Gross Upward Pricing Pressure Index) framework provides a measure of how the merger would affect the retailers’ incentives to increase prices, based on their profit margins and the extent to which customers treat them as close substitutes.[6]

However, this analysis does not factor in how the supplier would respond to such a merger. If the supplier doesn’t react, its profits will fall because when the merged retailer increases retail prices, it will reduce the volume of sales. Assuming the supplier was content with the pre-merger outcome, we might expect that it would want to influence retail competition post-merger to ensure overall market outcomes remain similar (and thus that its own profits do not fall).

The supplier’s ability to influence retail prices – even if it is a powerful monopolist – will depend on its pricing structure. If the supplier charges a single per-unit wholesale price (as illustrated in Pricing Structure A in Figure 1), then it cannot protect profits through price changes alone.[7] If it increases its wholesale price to compensate for lost sales, it would only reduce sales further (assuming that the retailer would pass some of those costs on to its customers). Alternatively, if the supplier lowers its per-unit wholesale price to protect sales (i.e., to maintain the retail price offered before the merger), then it will earn less profit because it maintains retail prices only by reducing its own profits, such that the merged retailer now takes a greater proportion of the same combined margin.

However, if the monopoly supplier charges a two-part tariff when selling its goods to the retailers (as illustrated in Pricing Structure B in Figure 1), then it can defend its profits against the impact of a merger. In a set-up with two-part tariffs, the supplier sets a per-unit wholesale price, w, and a fixed fee, F. This can enable the supplier to extract the entire monopoly profits in the industry. It will set the per-unit wholesale price at whatever point between marginal costs and the monopoly price it requires, so that (after the retailer’s margin is added) the final consumer price is at the level that a vertically integrated monopolist would set. The supplier then sets the fixed fee, which is not passed on in retail prices, to extract any difference between the profits it has already earned and the monopoly profits.[8]

Two-part tariffs can have benefits for both consumers and firms when there are risks of double marginalisation – that is, when both upstream and downstream firms have some market power. Relative to simple per-unit pricing, two-part tariffs mean that the downstream firm faces a per-unit price closer to marginal costs, and final consumer prices will be lower as a result. In practice, pricing and quantity agreements between suppliers and retailers can be quite complex, determining the product ranges retailers can sell, the quantities they receive, and the per-unit prices they have to pay. Formally though, these agreements may often look similar to two-part tariffs – the supplier sets a per-unit price along with further requirements which effectively impose a cost on the retailer that is not linked to the number of products it sells.

The supplier’s optimal balance between a fixed fee and a per-unit price will depend on the power of the retailers – i.e., the extent to which the retailer can add a margin on top of the wholesale price – and that balance will change following a merger between retailers. However, the monopoly supplier’s total profits will remain the same. It defends its pre-merger profits by reducing the per-unit price it charges to the retailers, and increasing the fixed fee. In addition, this will lead to little or no change in final consumer prices after the merger.[9]

To make this concrete, suppose that the supplier makes take-it-or-leave-it offers such that when a retailer purchases 2,000 units pre-merger, it pays the supplier £200,000 in total: £50 per unit and a fixed fee of £100,000. The retailer then sells each good to consumers at £100 per unit, making £50 gross profit per sale. Post-merger, the merged retailer may have an incentive (and ability) to increase its margin from £50 per unit to £60. To protect itself, the supplier responds: first, by reducing its variable wholesale price to £40, meaning that the retail price remains at £100 per unit (a £40 wholesale price and a £60 retail mark-up) and sales remain at 2,000 units; and second, by increasing its fixed fee to £120,000. Although the supplier’s revenue from wholesale fees has reduced to £80,000 (£40 x 2,000 units), the increase in its fixed fee maintains its total profits at the monopoly level.

We therefore find similar overall effects as in situations with buyer power – the pricing pressure that would normally result from a merger is reduced by supplier power. However, the route by which it happens is somewhat different. Rather than being entirely about the bargaining power of the supplier, the effect emerges because the supplier takes into account how the retail merger is likely to affect final prices when setting its prices to retailers. This means that supplier power, unlike buyer power, can eliminate the effects of a merger entirely, as in this example, rather than just mitigating them.

This is an extreme case, in which the monopoly supplier’s ability to make take-it-or-leave-it offers to retailers means that the retail merger has no effect whatsoever on final customer prices. In practice, as we discuss in more detail in our linked working paper, a supplier’s ability to alter the wholesale prices it offers is likely to mitigate the impacts of a downstream merger on retail prices, but not to eliminate them entirely. The scale of the effect depends in particular on:

- The extent of supplier market power. Where there are more alternative suppliers (e.g., suppliers of rival brands), the price impact of a retail merger is likely to be greater, since no individual supplier entirely internalises the effects of its pricing on final consumer prices.

- The balance of bargaining power between supplier and retailers (and how the merger changes this). If retailers can make take-it-or-leave-it offers to suppliers, supplier market power will have little effect. Moreover, if the merger changes the balance of bargaining power towards the retailers, this will reduce a supplier’s ability to mitigate consumer price rises through its pricing strategy.

- The pass-through rate between supplier wholesale prices and final consumer prices. This depends in turn on the shape of customer demand. When pass-through rates are low, the supplier’s ability to use wholesale prices to mitigate final consumer price rises is limited, meaning that a retail merger is likely to have a greater effect.

Application to merger assessment

Although the concept of supplier power has not yet entered into competition authorities’ merger guidelines, it has been discussed in some recent merger decisions. For instance, in its assessment of the planned merger between the sports good retailers JD Sports and Footasylum, the UK Competition and Markets Authority (“CMA”) noted that:[10]

“There are parameters of competition that Nike and adidas, the two most important suppliers, influence and, in some instances, actively monitor in order to ensure that their products are displayed, marketed and sold in the type of retail environment (whether in-store or online) that they consider benefits them. For example, these suppliers determine which retailers receive certain product ranges and the volumes that they receive. Suppliers set recommended retail prices (RRPs) which are generally followed by retailers. We have also found other aspects of [price, quality, range and service levels (PQRS)] that are influenced by suppliers.”

While recognising the role of supplier power and noting that “suppliers play an important role in shaping retail competition in this market,” the CMA ultimately concluded that “on balance, this constraint is not so significant as to sufficiently discipline the Merged Entity’s ability and/or incentive to deteriorate its offering post-Merger.” This was due to the evidence of some competition between retailers on PQRS; limits to suppliers’ ability to detect deterioration of PQRS post-merger; and no incentive on suppliers to discipline retailers where a deterioration of PQRS does not harm supplier interests.[11] The CMA prohibited the merger because it felt that it would lead to a substantial lessening of competition in the supply of sports footwear and apparel.

The CMA’s prohibition decision was partly based on its quantitative assessment of the pricing pressure that would result from the merger. It concluded that JD Sports exercised a strong competitive constraint on Footasylum, and that its GUPPI analysis indicated “a very strong incentive for the Merged Entity to worsen PQRS at Footasylum”. The CMA’s discussion of supplier power was qualitative; it did not incorporate supplier power effects into its GUPPI calculations.

Illustrative example of quantifying supplier power

Our working paper shows how supplier power effects can be integrated into GUPPI analysis, based on information about the extent of supplier power, the passthrough of wholesale prices to consumer prices, and the price sensitivity of customer demand. With this information, we can calculate a supplier-power adjusted GUPPI measure (SGUPPI), which takes into account how supplier reactions might be expected to change the impacts of a downstream merger.

Table 1, below, outlines an illustrative example (not based on any specific case) of how considering supplier power would change an analysis of the price effects of a downstream merger. In this case, looking at the retail market in isolation suggests that a merger between retailers A and B, or one between A and C, would lead to significant pricing pressure: 8% and 18% respectively. However, once we account for supplier power, the expected impact on retail prices falls substantially.

Table 1: Illustrative quantification of effects of supplier power

In this case, the GUPPI measure does not take into account the effect of the supplier’s ability to adjust its wholesale prices after the merger to maximise profits. As discussed above, if wholesale price changes are passed on to consumers in full, the supplier can completely offset the impact of the merger by reducing its wholesale price and increasing the fixed fee to an offsetting level. However, if – as in Table 1 – wholesale price changes are only partially passed through, the supplier cannot entirely eliminate the pricing effects of the merger, but it does attenuate them. On the SGUPPI, pricing pressure falls from 8% to 2.9%, which is less likely to raise concerns. In practice, such effects on pricing pressure need not be reflected only in retail prices, but may be seen in other dimensions that affect customer outcomes, such as the quality of the retail experience.

The extent to which supplier power offsets increases in retailers’ power will always depend on circumstances. Table 1 shows that a merger between retailer A and C would be very different from the merger of A and B. This is not just because this alternative merged retailer would have greater incentive to increase prices – its GUPPI is 18%, as opposed to 8%. In this case, pricing pressure remains relatively high even after taking supplier power into account, at 13.5%. This is because retailer C’s passthrough rate of wholesale prices is lower, meaning that the supplier is less able to influence retailer C’s consumer prices by changing its wholesale prices.

Retail mergers where there are powerful branded suppliers, such as fashion and sportswear markets, are obvious cases where it is important to consider the effects of supplier power. But the idea can be applied more widely. For instance, mergers in industries which are based on commodities supplied by oligopolistic markets, such as airlines, may also be affected by the extent of supplier power. Of course, this is not to say that consideration of supplier market power in itself would necessarily lead to different decisions. Rather, we argue that taking supplier power into account in such cases will be important for a full analysis of a merger’s impacts.

Supplier power is a neglected element of merger analysis, and raises questions that differ in some important ways from buyer power. When supplier power is absent, the standard upward pricing pressure approach to considering a merger’s impacts remains appropriate. However, as suppliers become more powerful, the GUPPI formula may overestimate the consumer harm resulting from the merger.

Read all articles from the Analysis

[1] We are grateful to Neil Dryden, who provided the inspiration for our work on this topic along with very helpful comments on the draft. The views expressed in this article are the views of the author only and do not necessarily represent the views of Compass Lexecon, its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, its employees or its clients.

[2] See, for instance, Inderst and Wey, “Buyer Power and Supplier Incentives”, European Economic Review, April 2007 (vol.51, issue 3), pp. 647-667.

[3] European Commission, Guidelines on the assessment of horizontal mergers under the Council Regulation on the control of concentrations between undertakings, (Official Journal C 031, 05/02/2004 P. 0005 – 0018), paragraphs 64-67.

[4] Michael E. Porter, "How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy", Harvard Business Review, May 1979 (Vol. 57, No. 2), pp. 137–145.

[5] For a technical discussion of these issues see: Perkins and Shekhar (2021), “Horizontal Mergers and Supplier Power”, available on SSRN at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3836463.

[6] Farrell and Shapiro, “Antitrust Evaluation of Horizontal Mergers: An Economic Alternative to Market Definition”, The B.E. Journal of Theoretical Economics, 2010 (vol. 10, issue 1), pp.1-41.

[7] It might, for instance, be able to increase the amount it supplies to a competing retailer.

[8] Our model applies to the canonical circumstances where prices are set according to marginal costs, and companies will seek to cover their fixed costs from the gross margin they are able to charge. As discussed by Lau Nilausen https://www.compasslexecon.com..., both in principle and in practice, the costs that companies consider “marginal” will depend on the relevant time horizon. In the example of retailers of consumer goods, it will often be a reasonable approximation to assume that a retailer prices its goods by reference to the cost of one additional product. To the extent that retailers take into account their fixed costs when setting prices, the impact of supplier power may reduce somewhat.

[9] There may be small changes to final prices (positive or negative) depending on the shape of customer demand and the nature of differentiation between retailers.

[10] Competition and Markets Authority, Completed acquisition by JD Sports Fashion plc of Footasylum plc: Final report on the case remitted to the CMA by the Competition Appeal Tribunal (2021). Paragraph 12. Available at (accessed 6 June 2022): https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/61851fa0e90e07197483b953/JD_FA_Final_Report_5.11.21.pdf.

[11] Competition and Markets Authority, Completed acquisition by JD Sports Fashion plc of Footasylum plc: Final report on the case remitted to the CMA by the Competition Appeal Tribunal, Appendices and Glossary (2021). Appendix I, paragraphs 2.73 to 2.75. Available at (accessed on 6 June 2022): https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6131cf158fa8f503c6403d51/Appendices_and_Glossary_final_1.pdf,.