Investment disputes in the crossfire of War – Part II: the impact of Russian “Countersanctions” on value

Share

In the series “Investment Disputes in the Crossfire of War”, economists from Compass Lexecon’s International Arbitration practice discuss challenges arising in the valuation of damages amidst Russian geopolitical shifts.

This second article explores some of the key measures—so-called “countersanctions”—introduced by Russia since the invasion in Ukraine in February 2022, particularly those related to currency conversions and the repatriation of returns outside Russia. Whether these countersanctions constitute breaches for the purpose of commercial or investor-state arbitrations, or solely provide economic background, they can have a significant impact on the value of assets and companies in Russia. Economists Julian Delamer and Vladimir Tsimaylo [1] share their insights.

Introduction

The number of sanctions against Russian individuals, companies, investments, and trade following the invasion of Ukraine, which began on 24 February 2022, is often described as “unprecedented” due to their sheer scale, targeting almost 13,000 individuals and more than 8,000 entities as of January 2025.[2]

Moreover, under pressure from investors and consumers, many Western companies unwound their investments, closed stores, and paused sales in Russia. Hundreds of companies exited the country, reportedly incurring an estimated $100–300 billion in losses.[3] However, these measures were not left unanswered by Russia, which introduced a series of “antisanction measures” or “countersanctions” ranging from restrictions on business activities to direct expropriations. These measures have led to multiple contractual and treaty disputes around potential damages which require independent opinions of quantum experts.

The landscape of EU, UK, and US sanctions packages, alongside Decrees issued by the Russian President and Orders of the Russian Government, is constantly evolving and is closely monitored by multiple law firms that provide regular updates. In this article, we first provide a brief overview of Russian legislation affecting the valuation of foreign investments in Russia since February 2022, focusing on Russian retaliatory measures related to cross-border operations. The objective of this overview is not to be exhaustive, but rather to set out the context for ensuing discussion of quantum-related challenges this may entail, in particular leveraging the lessons for quantum experts set out in the first part of this series, “Insights from Crimean Arbitrations”.

Countersanctions targeting cross-border operations

A taxonomy of countersanctions

As early as 2018, Russia adopted a legal framework allowing measures against countries deemed to have engaged in “unfriendly” actions. The scope of potential measures included (but was not limited to) restrictions or bans on international trade, as well as limitations on economic interactions with the Russian state.[4] By 2021, this framework crystallised in the first “unfriendly countries list”, which included the US and Czechia, although no economic measures were applied at that time.

After February 2022, however, Russia added a further 48 jurisdictions and considerably expanded the range of measures targeting “unfriendly” foreign states and persons either associated with them or under their control.[5] As of May 2025, the countersanctions universe encompasses more than 180 Presidential Decrees, almost 1,000 Resolutions and Orders issued by the Government of Russia, and more than 450 new Federal Laws, supplemented by hundreds of additional bills, clarifying statements, and press releases from the Ministry of Finance and the Bank of Russia.[6]

Leaving aside measures targeting specific foreign individuals, media outlets, and international organisations—or supporting certain groups of Russian citizens and industries—the countersanctions relevant to the operations of foreign businesses can be broadly categorised into four groups:[7]

- Cross-border operations regulations, including new controls over capital flows and foreign currency transactions, exchange rates, cash withdrawals, remittances, and payment terms for international transactions;

- Equity deals and assets ownership measures, ranging from additional procedural requirements to relinquish ownership of Russian assets and bans on transactions of certain shares, to external administration and outright nationalisation;

- Trade and customs regulation, introducing limitations on specific types of imports and exports, including general and targeted bans, export permit requirements, and restrictions on border crossing points; and

- Relaxed IP regulation, such as reduced liability for the unauthorised duplication of copyrighted content (and parallel imports more generally) and the termination of certain Civil Code provisions protecting the exclusive rights of trademark owners.

In this article, we focus on the first group of countersanctions and the implications of the measures affecting currency conversions and the transferability of cash flow distributions outside Russia. These were initially introduced through two Presidential Decrees, with their application subsequently expanded by follow-up regulations. In future articles we will explore other countersanctions.

Cross-border operations regulations

As early as 28 February 2022, the Russian President signed Decree No. 79 introducing currency controls aimed at stabilising the ruble’s exchange rate. Among other measures, it prohibited Russian residents involved in export and import contracts from granting foreign currency loans to non-residents under loan agreements, and from crediting foreign currency to their overseas accounts held with banks and other financial organisations.[8]

Decree No. 95, signed on 5 March 2022 (with the latest amendments made in January 2025), went one step further and imposed a “temporary procedure” for the repayment of foreign debt to entities from “unfriendly” states or those controlled by them.[9] This procedure was later expanded to cover profit distributions (Decree No. 254), air transport and equipment leasing payments (Decree No. 179), as well as Eurobond settlements (Decrees No. 430 and No. 665), and introduced:[10]

- A currency conversion restriction: if a Russian resident—a citizen, a company, the state itself, or its regions and municipalities—is required to make a cash distribution (to settle a debt or a lease obligation, or to pay out dividends) above a certain threshold, such a payment must be made in rubles to a special bank account.

- A transferability restriction:

- Upon transfer, the creditor is entitled to make a claim for the use of the paid funds, subject to the rules established by the Central Bank of the Russian Federation (for financial organisations) or the Ministry of Finance of the Russian Federation (for all other companies).

- These rules limit the use of such funds to the payment of taxes and statutory fees in Russia, the acquisition of Russian sovereign debt, and transfers to other special bank accounts. The special bank account regime does not allow for the funds to be transferred abroad.

- The Central Bank of Russia and the Ministry of Finance were granted authority to exempt companies from these restrictions and to issue permissions for cash distributions (to settle a debt or a lease obligation, or to pay out dividends).

From 1 April 2022, a special procedure was also established for the fulfilment of obligations to Russian natural gas suppliers by foreign buyers from “unfriendly” countries.[11] In particular, payments for natural gas were required to be made in rubles into special accounts with authorised banks (such as Gazprombank, which was the only authorised bank until further sanctions in December 2024).[12] If the payment deadline under a gas supply contract expired, or if payment was not made (in full) or was made in a foreign currency, the gas supply could be prohibited.[13]

In sum, since 2022 Russia has put in place a wide range of rules that make it harder for foreign businesses from “unfriendly” countries to move money out of Russia. These include forcing certain payments—like dividends or debt repayments—to be made in rubles into restricted accounts that do not allow transfers abroad. Even when payments are made, Russian authorities tightly control the use of the funds. These restrictions are part of a much broader response by Russia to Western sanctions and now form a complex and evolving legal environment that foreign investors must navigate.

The economic impact of countersanctions

The countersanctions on cross-border operations have made the lawful repatriation of proceeds from Russia uncertain and conditional on regulatory decisions. These measures affected both global investors who decided—or were compelled—to abandon their operations in Russia (whether due to sanctions, countersanctions or shareholder votes), as well as businesses that have continued to operate within the country.

Although there is no confirmed figure for the number of firms from “unfriendly” states that have exited or remain active in Russia, there is substantial evidence that all have suffered significant valuation losses.[14]

- According to estimates from Interfax, by the end of 2022, oil and gas companies alone had recorded impairments of approximately $58 billion on their Russian assets, mostly due to asset write-offs. This figure reflects a combination of value losses resulting from sanctions, retaliatory measures, and business exits.[15]

- Despite having reduced their exposure to Russia over the preceding decade, international investment banks remained vulnerable to Russian securities and retail financial products, with the wind-down of these positions resulting in billions of dollars in losses.[16]

- Foreign companies that elected to remain active in Russia generated an estimated combined revenue of more than $127 billion in 2022, amassing more than $18 billion in earnings that remained trapped within the country.[17] In 2023, these companies reportedly generated $197 billion in revenue and $17 billion in profits.[18]

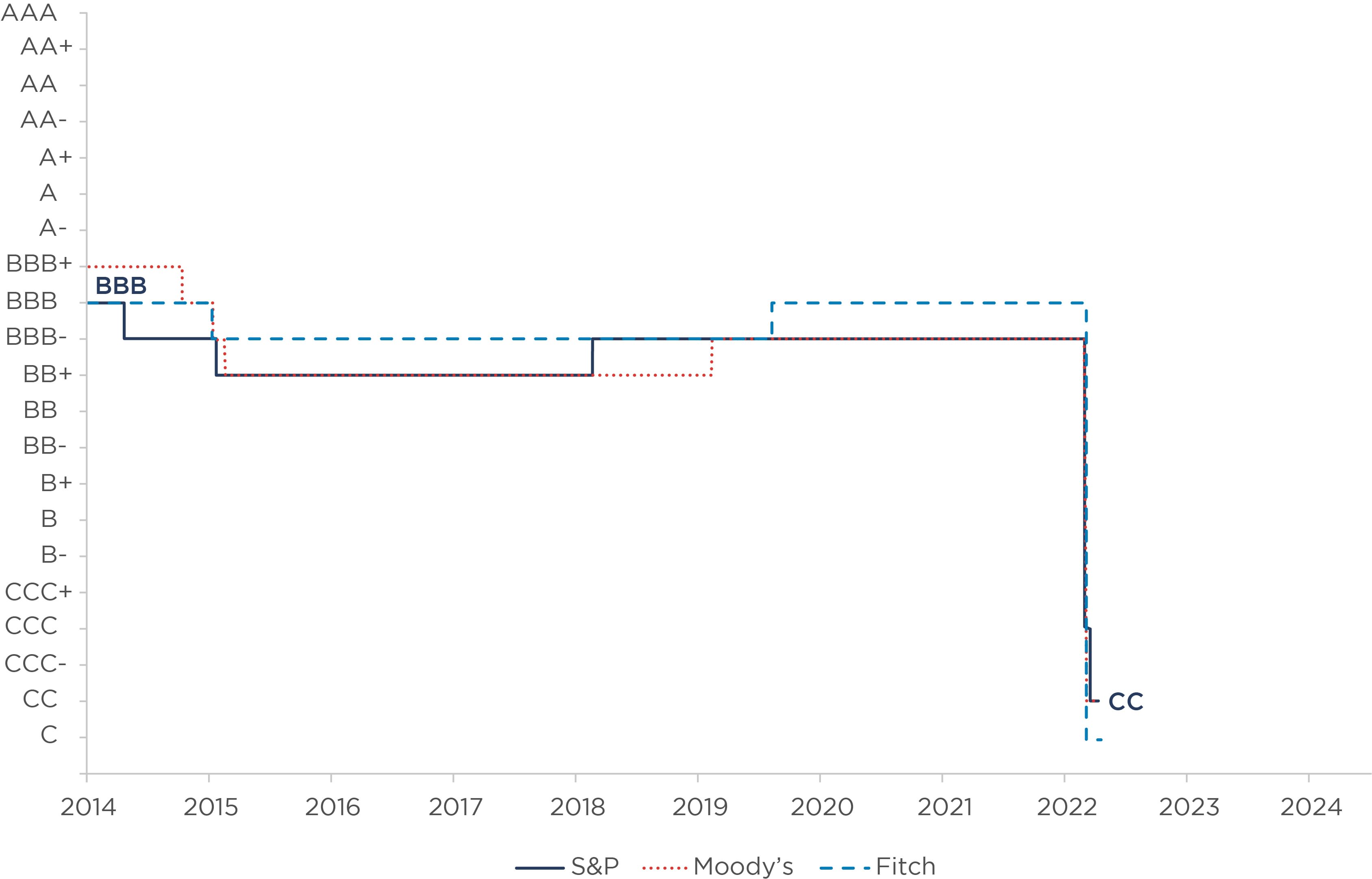

Furthermore, the combined effects of sanctions and countersanctions contributed to the general worsening of the market environment, as evidenced by Russia’s downgraded (and eventually withdrawn) sovereign credit rating, shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Russia’s sovereign credit rating by major credit rating agencies

Initially, Russia’s sovereign rating was downgraded from BBB-/A-3 to BB+/B with a negative outlook immediately following the military intervention. This reflected the anticipated impact of newly announced sanctions and heightened geopolitical uncertainty on foreign trade and economic activity, domestic and private-sector confidence, financial stability, and growth.[19] Subsequent international sanctions targeted the foreign exchange reserves of the Central Bank of Russia—rendering them inaccessible and impairing Russia’s net external liquidity position. In response, Russia introduced capital controls through countersanctions, leading to a further downgrade to CCC-.[20]

When investors did not receive a coupon payment on Russia’s dollar-denominated Eurobonds in mid-March 2022, the sovereign rating was further reduced to CC.[21] In accordance with Decree No. 95, the Russian government made coupon and principal payments in rubles to the National Clearing Centre, an action considered a selective default.[22] Ultimately, Russia’s sovereign credit ratings were withdrawn altogether.

In parallel, the currency controls took hold in natural gas markets, forcing buyers to settle gas purchases in rubles or to convert foreign currencies through Gazprombank. This led to contractual disputes, which were exacerbated by the explosions of the Nord Stream pipelines in 2022. Consequently, Gazprom abruptly ceased gas deliveries to several European buyers. In recent years, more than a dozen European energy companies have initiated legal proceedings against Gazprom, seeking approximately €18 billion in damages to compensate for losses incurred as a result of the suspension of Russian gas supplies.[23]

Overarching quantum challenges

Russia has entered into multilateral treaties (such as the Energy Charter Treaty) and bilateral investment treaties (BITs) with more than 80 states, including with countries designated as “unfriendly” in the context of the countersanctions.[24] These BITs contain several standards of protection for foreign investors and their investments, including fair and equitable treatment (FET), most-favoured nation (MFN) treatment, and the free transfer of investments and returns to the investor’s home country.[25] These may become relevant in the context of Russia’s countersanctions, which may adversely affect the value, profitability, and viability of foreign investments in Russia.

Whether they are directly claimed as measures in the context of international arbitration or merely form part of the macroeconomic backdrop to other disputes, Russian countersanctions on currency and capital flows pose several challenges for quantum experts tasked with providing a fair market valuation of real or financial assets.

Three critical considerations that would affect any such analysis relate to: (i) identifying contemporaneous investors’ expectations; (ii) assessing investment risks; and (iii) handling data restrictions.

Assessing contemporaneous investors’ expectations

While it is for legal experts to determine whether the countersanctions were retaliatory—in response to sanctions triggered by the invasion—and whether they qualify as pre-existing conditions to other claimed measures, it falls to the quantum expert to translate the legal positions into workable valuation scenarios. One of the lessons we identified from the Crimean arbitrations is that “[t]he skill of a quantum expert manifests in translating, within what can be an intricate factual background, the legal claims into sound actual and counterfactual scenarios which properly encapsulate the impact of the claimed measures.”[26]

As with the Crimean arbitrations, investors’ expectations in Russia have evolved considerably in recent years. The invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 triggered significant market disruptions and heightened uncertainty within Russia. This occurred alongside a looming energy crunch in Europe marked by surging electricity and commodity prices, persistent post-Covid bottlenecks in supply chains, and worsening inflation—factors arguably further exacerbated by the invasion itself. Additionally, businesses operating in Russia were affected by foreign sanctions directly (e.g., through trade bans) and indirectly (e.g., through the unavailability of vital insurance coverage on international markets).

Over time, however, markets adapted to the new restrictions and altered supply chains, while the Russian economy maintained a steady, and even growing, state.[27] Despite the collapse of trading, technology, and transport links with Western economies, the cash flow-generating ability of the remaining businesses was supported by decreased competition and growing disposable income among Russian consumers. In 2024, the MOEX Russia Index [28] briefly returned to pre-invasion levels, partly fuelled by trapped domestic savings, but also reflecting diverging outlooks between domestic and foreign investors.[29]

Figure 2. MOEX index, 2021 - 2025

Identifying market expectations as of the relevant valuation date—particularly concerning the anticipated impact, duration, and enforceability of countersanctions on currency conversion and the transferability of cash distributions—is of critical importance in damages assessments (see Lesson [1] from the Crimea Arbitrations article). While such expectations would typically be embedded in asset prices in efficient markets, this is not necessarily the case in imperfect and/or illiquid markets. It is therefore incumbent upon the quantum expert to gather contemporaneous evidence that captures investors’ risk appetite, consumption preferences, information uncertainty, and perceptions of macroeconomic risk at the relevant time.

An example of evolving investor expectations affected by a dynamic macroeconomic and regulation environment is the business of Corinthia Group, which owned and managed a portfolio of hospitality and commercial assets mostly located in St Petersburg. While demand was driven mostly from Russia and was therefore initially unaffected by the restrictions on international travel, the Group had to recognise a fair value loss on the portfolio in 2022 as a result of the increased uncertainty. Being headquartered in Malta, an “unfriendly” state to Russia, the Group had to fast-track the settlement of outstanding bank loans in Russia to avoid some of the countersanctions. The contribution of Russian assets to total revenues more than halved due to the depreciating ruble. However, while the outlook remains uncertain, in 2024 the Group increased a carrying amount of the assets due to increasing occupancy levels “in view of the local trade”.[30]

Assessing investment risks

A key responsibility of quantum experts is isolating the impact of the claimed measures from other factors which affect value but are not directly related (similar to Lesson 2 of the Crimea Arbitration article). The valuation of investments in Russia has been complicated by countersanctions on cross-border operations. First, the ruble ceased to be a freely traded currency, and the ban on capital withdrawals effectively served as a form of currency reserve.[31] Second, as noted above, Russia’s sovereign credit ratings were withdrawn, and the country entered into a “technical” default due to external and internal transaction restrictions.

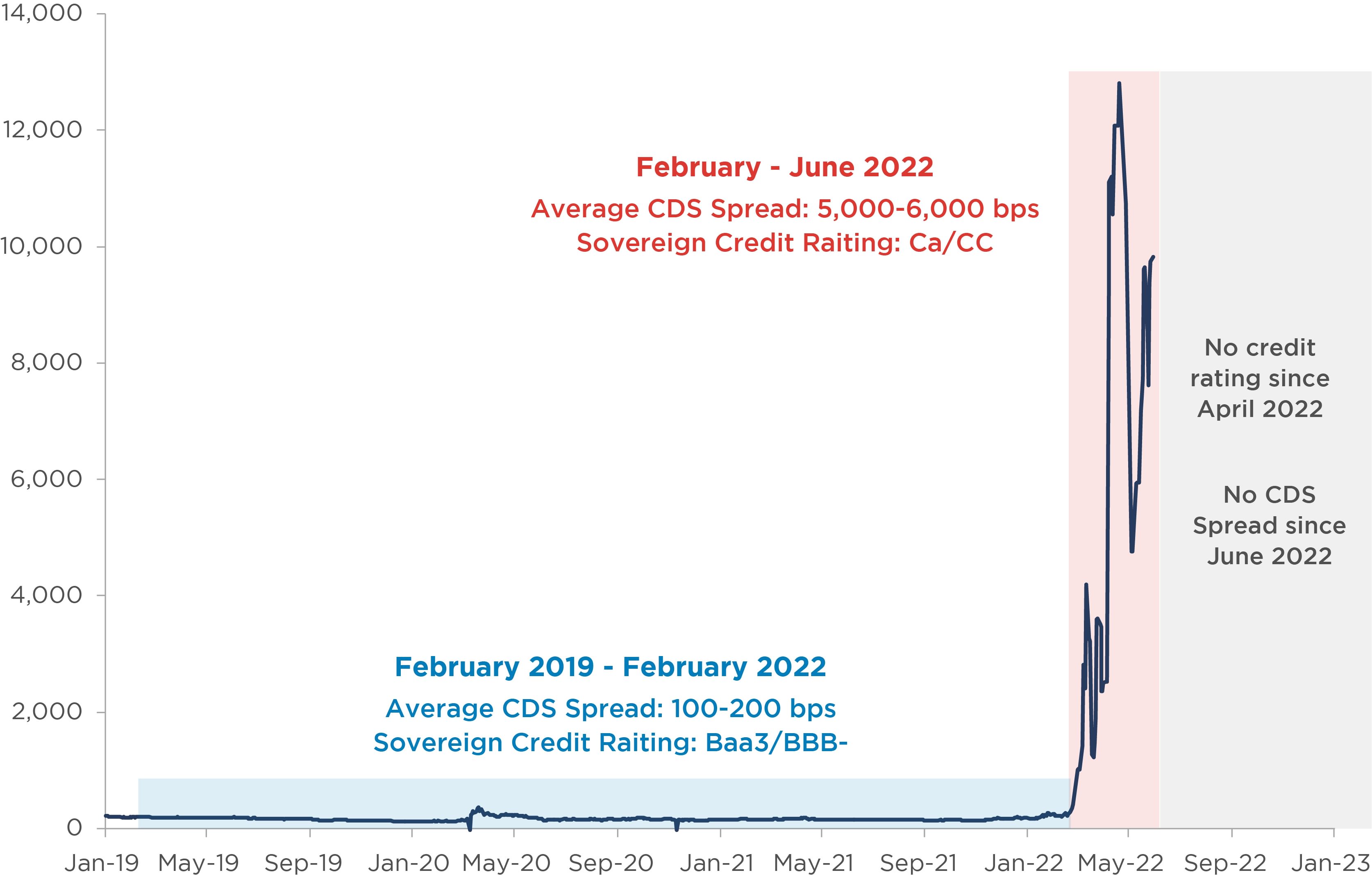

These developments make it particularly challenging to assess the specific risks of investing in Russia (as opposed to a different jurisdiction), which are typically captured through a country risk premium—i.e., the additional return required to compensate investors for jurisdiction-specific risks relative to the safest economies.[32] This task has been further complicated by the inaccessibility of traditional alternatives such as credit default swap (CDS) spreads, which typically provide more timely and precise indicators of default risk than sovereign bond spreads.[33] As shown in Figure 3 below, Russia’s CDS spreads rose dramatically in the spring of 2022 before becoming unavailable after June 2022.

Figure 3. Russian country risk premium and average CDS spread, bps, 2019 - 2022

Despite the lack of comprehensive data, valuations have continued over the past three years, notably in the context of foreign investors selling their assets in Russia. In light of the restrictions on currency conversions, such valuations have generally relied on yields from sovereign bonds denominated in rubles, which Russia has not defaulted on.[34]

Nonetheless, numerous questions arise when assessing investment risks in the context of damages estimation. For instance, do the yields of ruble-denominated sovereign bonds fully reflect the return expectations of a willing buyer and an uncoerced seller in an arm’s-length transaction? How should increased reputational risks and financing restrictions be factored in? To what extent had Russia’s country risk premium already reflected the impact of the invasion and countersanctions as part of the assumed political or emerging market risk?

Furthermore, the impact of sanctions and countersanctions is not uniform across all asset classes, meaning a one-size-fits-all adjustment via the discount rate may lead to imprecise valuations. In some cases, it may be more appropriate to reflect the effects of specific, heterogeneous measures through the cash flows—such as by using scenario analysis or applying probability weights to different possible policy paths.

Adapting to data constraints

In addition to the withdrawal of sovereign credit ratings, Russian authorities have restricted access to, or entirely deleted, vast swathes of data to support the implementation of countersanctions. This has severely limited the capacity for independent research, external analysis, and standard due diligence procedures.

Such data concerns are common in arbitration cases (see Lesson 3 of the Crimea Arbitration article); quantum experts should not be deterred by these difficulties and use available data and techniques to aid the tribunal.

According to some estimates, between 2022 and 2024, nearly 600 datasets were removed from the public domain. Furthermore, the State Duma passed legislation authorising the Government to cease publication of any federally collected data, such as oil production and refining figures, which have been unavailable since 2023.[35] With several international data providers also withdrawing from Russia, analysts have increasingly lost the means to verify the reliability of the remaining information.[36]

Among the datasets concealed or no longer updated, examples particularly relevant for valuation practitioners include:[37]

- corporate filings of stock market participants;

- ownership data from the Unified State Register of Real Estate;

- electricity consumption data;

- airport passenger flows;

- banks’ financial statements and corporate governance data for other financial organisations;

- government budget income and expenses; and

- monthly customs data on Russia’s exports, imports, and capital flows structure.

In addition to allowing Russian companies to withhold otherwise public corporate governance and financial information, new regulations have restricted access to information about subsidiaries of Russian companies if they are owned or controlled by entities (potentially) subject to sanctions.[38]

In light of non-existent or severely limited data, it is not uncommon for valuation professionals to resort to alternative datasets and methodological shortcuts. As noted in the first article of this series, several Crimean arbitrations faced similar difficulties following the loss of physical access to evidence left behind in nationalised properties.[39] Comparable challenges have arisen in disputes stemming from the Covid-19 pandemic—when uncertainty placed some markets into a “frozen state” with no transactional data—or from market manipulation cases, where experts had to reconstruct hypothetical efficient markets.

In these circumstances, valuation practitioners have to deploy certain tools to address evidentiary gaps. Examples include:

- using long-term averages, adjusting for externalities and seasonality if necessary;

- inferring parameters though the use of comparables, adjusting for any idiosyncrasies of the target asset; and

- deploying regression analysis, as properly calibrated econometric tools fed with historical data can be used to simulate market price and demand dynamics, for example.

While inferred, estimated or simulated parameters may introduce greater uncertainty than the use of actual data, they can still represent the best available evidence to a tribunal if faced with data limitations. If the methods used to obtain such estimations are sound, these parameters may still provide a sufficiently reliable basis for assessing quantum.

Conclusion

In summary, countersanctions have introduced new challenges and significantly increased the complexities related to estimating the fair market valuations of real and financial assets in or linked to Russia. Quantum experts must navigate evolving investor expectations, heightened and opaque investment risks, and substantial data constraints when constructing both actual and counterfactual valuation scenarios.

As established in our article on the Crimea Arbitrations, quantum experts should not be deterred by these difficulties but should learn from previous experience to best assist the tribunal. While traditional tools and assumptions may no longer be fully applicable, careful reconstruction of market conditions using contemporaneous evidence, adjusted risk assessments, and creative but rigorous methodologies ensures that reliable valuations remain achievable even under unprecedented circumstances.

References

-

Julian Delamer is an Executive Vice President and Vladimir Tsimaylo is a Senior Economist at Compass Lexecon. The views expressed in this article are the views of the authors only and do not necessarily represent the views of Compass Lexecon, its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, its employees or its clients.

-

See Reuters. “Foreign firms' losses from exiting Russia top $107 billion”, dated 28 March 2024. See also Izvestia “Dmitriev pointed to the loss of $300 billion by US businesses after leaving the Russian market”, dated 18 February 2025.

-

See Federal Law No. 127 FZ “On Measures (Countermeasures) in Response to the Unfriendly Actions of the USA and/or Other Foreign States”, dated 4 June 2018.

-

On 5 March 2022, the Russian government issued Order No. 430-r attaching a list of “Foreign States and Territories Involved in Committing Unfriendly Actions Against the Russian Federation, Russian Legal Entities and Natural Persons”, which included among others the UK, EU Member States, and the USA.

-

The full list available here: https://base.garant.ru/5775063....

-

Among many other measures there are restrictions on access to Russia’s inland waters and seaports, a moratorium on bankruptcy, administrative and criminal liability for discrediting the army, and the exclusive jurisdiction of Russian state courts over sanctions-related disputes.

-

The outright ban was later replaced with a limitation on the transactions subjected to the pre-clearance by a special Government Commission. See Decree No. 79 "On Special Economic Measures in connection with Unfriendly Actions by the United States of America and the Foreign States and International Organizations that have Joined Them," dated 28 February 2022. See also Decree No. 81 "On Additional Temporary Economic Measures to Secure the Financial Stability of the Russian Federation", dated 1 March 2022.

-

See Decree No. 95 "On the Temporary Procedure for the Performance of Obligations to Certain Foreign Creditors," dated 5 March 2022.

-

See Decree No. 179 “On the temporary procedure for fulfilling financial obligations in the field of transport to certain foreign creditors”, dated 1 April 2022. See also Decree No. 254 “On the temporary procedure for fulfilling financial obligations in the sphere of corporate relations to certain foreign creditors”, dated 4 May 2022. See also Decree No. 430 "On the repatriation of foreign currency and the currency of the Russian Federation by residents - participants in foreign economic activity", dated 5 July 2022.

-

See Decree No.172 "On a special procedure for the fulfillment by foreign buyers of obligations to Russian suppliers of natural gas", dated 31 March 2022.

-

See Decree No. 1033 "On Amendments to the Decree of the President of the Russian Federation of 31 March 2022 No. 172 "On a Special Procedure for the Fulfillment of Obligations by Foreign Buyers to Russian Suppliers of Natural Gas", dated 4 December 2024.

-

The debts of the buyers were later permitted to be settled in foreign currency. See Decree No. 922 “On Amendments to the Decree of the President of the Russian Federation of 31 March 2022 N 172 "On a Special Procedure for the Fulfillment by Foreign Buyers of Obligations to Russian Suppliers of Natural Gas"”, dated 30 December 2022.

-

An academic debate remains over the correct way of measuring the “exits” with some outfits counting only the discontinued legal entities and others including closed branches too. As a result, the Yale School of Management estimates 1,028 companies have fully left Russia as of July 2023, while the Kyiv School of Economics estimates just under 500 companies have left Russia, with more than 1,800 remaining as of April 2025. See https://www.yalerussianbusines... and https://leave-russia.org/.

-

See Interfax. “Foreign oil and gas companies suffered almost $58 billion in losses from asset depreciation in Russia”, dated 6 March 2023.

-

NYT “Companies Are Getting Out of Russia, Sometimes at a Cost”.

-

See FT. “Billions of dollars in western profits trapped in Russia”, dated 18 September 2023.

-

See KSE Institute. “Foreign business exit from Russia continues, but over 2,200 companies still fuel its economy”, dated 7 February 2025.

-

See S&P. “Russia Foreign Currency Rating Lowered To 'BB+' And Put On CreditWatch Negative On Risks Related To Invasion Of Ukraine”, dated 25 February 2022.

-

See S&P, “Russia Ratings Lowered To 'CCC-' And Kept On CreditWatch Negative On Increasing Risk Of Default Table of Contents”, dated 3 March 2022.

-

See S&P “Research Update: Russia Foreign And Local Currency Ratings Lowered To 'CC' On High Vulnerability To Debt Nonpayment, Still On Watch Neg”, dated 17 March 2022.

-

See S&P “Russia Foreign Currency Ratings Cut To 'SD', Local Currency Ratings Kept At 'CC'; All Ratings Subsequently Withdrawn”, dated 8 April 2022.

-

See EUToday. “Gazprom faces €18 billion in claims from European energy firms over gas supply cuts”, dated 11 March 2025.

-

See the full list here: https://investmentpolicy.uncta....

-

It is important to note that the specific language of different treaty standards varies from one BIT to another. Accordingly, the scope of protection offered by one treaty under the different treaty standards may be limited in comparison to the protection offered by another treaty.

-

See Delamer J., Tsimaylo V. “Investment disputes in the crossfire of War - Part I: Insights from Crimean Arbitrations”, dated 25 February 2025.

-

See BBC “Russia to grow faster than all advanced economies says IMF”, dated 16 April 2024.

-

Moscow Exchange Index is a capitalisation-weighted composite index that tracks the performance of the 50 largest Russian companies listed on the Moscow Stock Exchange.

-

See FT “Russia’s trapped domestic investors push stock market to 12-month high”, dated 28 April 2023.

-

See 2021-2024 Annual Reports of Corinthia Group, note 5.2.

-

As a result of further US sanctions, forex trading has been suspended on Russian financial marketplaces since mid-2024 and has moved over-the-counter. See Reuters. “Rouble swings to opaque trading territory after new US sanctions”, dated 13 June 2024.

-

See Forbes, “Risks of investing in Russian stocks have doubled since the start of the “special operation”, dated 12 December 2023.

-

See Damodaran A. “Equity Risk Premiums (ERP): Determinants, Estimation, and Implications – The 2023 Edition”, dated 32 March 2023.

-

See RBC “Russia's investment risk premium returns to pre-crisis levels”, dated 19 February 2025. See also Avi Group Research “Using OFZ as a risk-free rate for WACC and CAPM”, dated 12 March 2024.

-

See Tochno.st “76 datasets have been removed from government websites since the start of the year”, dated 10 June 2024.

-

See The Bell, “The authorities are afraid of this data being made public – how Russia hides economic statistics”, dated 14 May 2022.

-

See Tochno.st “Over the past two years, 44 government agencies have removed nearly 500 datasets from their websites. Final update of the open data tracker”, dated 29 December 2023.

-

See Gherson News & Blog “Russia amends law which will likely impact UK companies’ due diligence processes”, dated 6 February 2025.

-

See Delamer J., Tsimaylo V. “Investment disputes in the crossfire of War - Part I: Insights from Crimean Arbitrations”, dated 25 February 2025.