Tariffs versus Contracts

Share

The new tariff environment creates unique challenges for the supply chains supporting US trade. Market adjustment processes based on economic theory may run afoul of contractual rigidities, triggering a higher potential for disputes. Our team routinely analyzes how unexpected regulatory changes impact business dynamics and value to stakeholders, and has the expertise to help navigate this challenging new environment. [1]

The views expressed in this text are the sole responsibility of the authors and cannot be attributed to Compass Lexecon or any other parties.

In 2024, US trade volume represented around 6.5% of global GDP (with USD 4.1 trillion in imports and USD 3.2 trillion in exports). [2] This substantial volume of trade is the product of long-term international supply chains developed over the last 50 years, a large portion of which are structured around contractual agreements that set volumes or prices (or both). In many cases, contracts will not be able to adapt to the changes in market conditions and trade policies, generating tensions between partners and raising the possibility of disputes.

To contextualize why this may be the case, it is necessary to consider the basic economics of tariffs. Tariffs are a particular type of tax in which the object of taxation is, in principle, the foreign manufacturer of an imported good. However, since governments have no jurisdiction to tax foreign entities, the tax must be paid on the imported good at the point of entry. This means that the contractual responsibility for the payment of tariffs will, in most cases, fall on the importer.

There is a key distinction between tax impact (i.e., who has the legal obligation to pay the tax) and tax incidence (i.e., who ultimately bears the burden for the tax through changes in net prices or volumes). In economic terms, whether the buyer or the seller absorbs more of the tax depends on their ability to modify behavior (i.e., quantity demanded or supplied) when faced with changes in prices, otherwise known as price elasticity. Whoever has a higher price elasticity will be able to pass more of the tax impact to the counterparty.

The tax incidence may change significantly in the medium to long term as price elasticities evolve. For example, if tariffs affect agricultural imports, for which the US constitutes a sizable portion of global trade, non-US farmers will be limited in their ability to modify supply for the current crop season, while US consumers will most likely reduce consumption in response to higher prices. As such, the heavier tax incidence will fall on non-US farmers. For subsequent seasons, however, farmers will reduce crop quantities when faced with the lower net price, and will look for alternative markets and/or uses for their production. Consequently, the supply elasticity will increase, and a larger portion of the tax incidence will be transferred to US consumers.

The converse could also be true. If a car manufacturer buys certain specific car parts from overseas, it will likely have to absorb most of the impact of the tariffs in the short run, as it will have little to no ability to substitute the specific parts with a new supplier. [3] Beyond the short term, however, alternative supply chains or product redesigns will increase demand elasticity.

Overall, tariff incidence, particularly in the short term, will depend largely on the ability of exporters and importers to adjust their trading relationships. This is because supply chains have inertia and will take time to adapt to the new trade flow. The transition to a long-term equilibrium is, in this case, lengthened by the relative size of the US economy and its participation in world trade, which could give US importers and exporters a temporary advantage in terms of bargaining power to transfer more of the tax incidence to their trade counterparties.

These tariff burden dynamics may conflict with rigidities imposed by contractual terms. The Incoterm rule in each contract (i.e., the rule establishing at which point goods are delivered to the importer) [4] determines which of the contracting parties is obligated to pay the tax:

- If the Incoterm rule is FOB, CIF, or ex-works (which are the most common definitions), the seller (exporter) is not responsible for the tariff and will demand the full payment of the contractual price. As the exporter will have a contractual ability to transfer the complete burden of the tariffs, the importer will see how the cost of continuing to buy from its contractual counterparty diverges from the market price. In such cases, the buyer (importer) will have strong incentives to attempt a renegotiation.

- If the seller (exporter) is responsible for the tariff by having a Delivered Duty Paid (DDP) Incoterm obligation, the opposite situation exists, and the exporter will want to demand more than the contractual price from the buyer (importer) in order to cover the cost of the tariff.

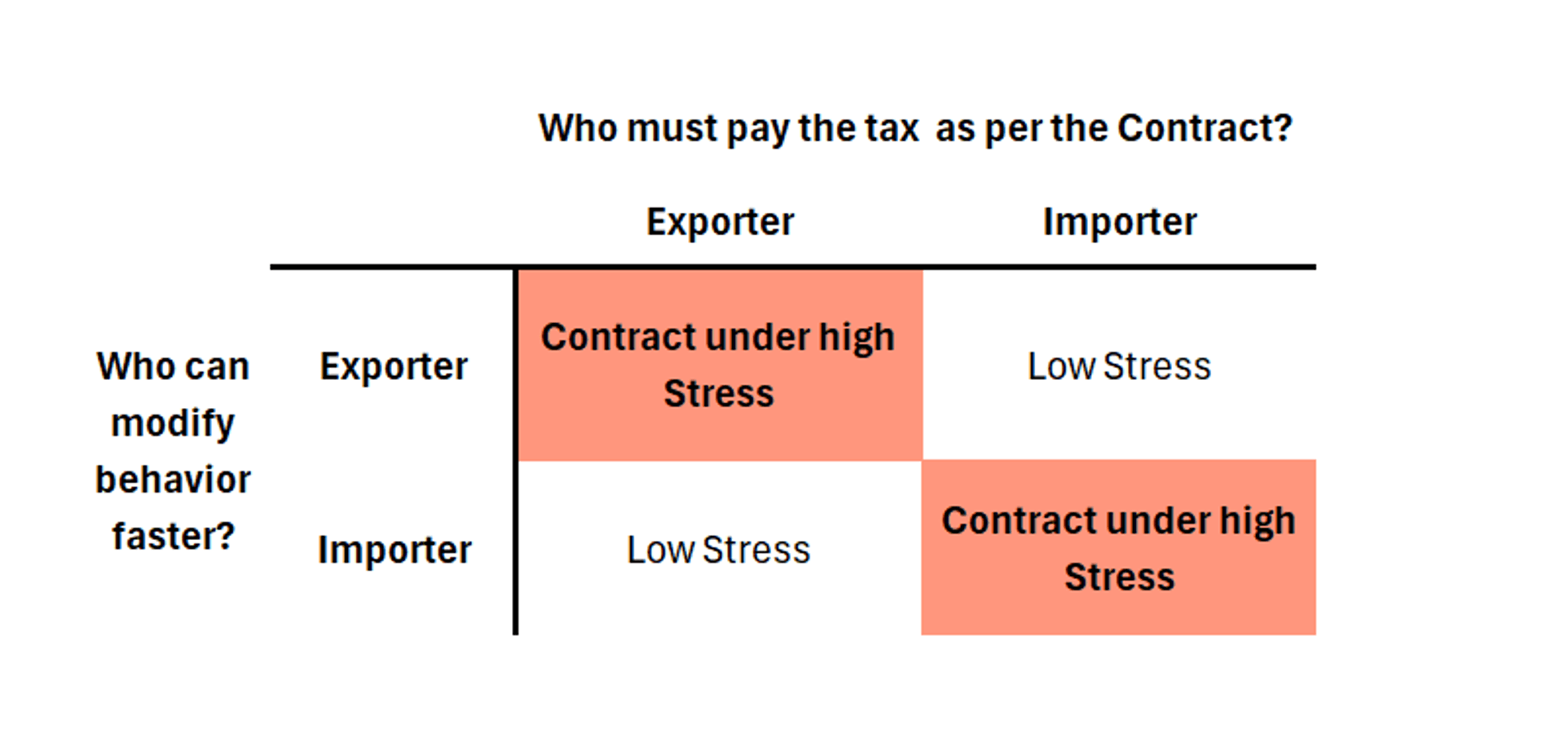

The contractual relationships more prone to tensions are those where the contractual responsibility for payment falls on the party that has a higher ability to modify its behavior.

Figure 1: Tariff Tension Matrix

Contractual dynamics may also be affected by force majeure type analysis. Specialized US exporters can risk their economic viability by refusing to absorb tariffs (if this would mean losing access to the import market). But even if they agree to absorb the tariffs, the price reductions may eliminate their value (particularly when fixed costs were needed at the onset of the relationship). From the importer side, absorbing tariffs may reduce profitability (by either resulting in lower net prices or decreased volumes), but their viability will only be put at risk if they import the lion’s share of their inputs.

In sum, while contracts establish responsibility for tariff payments, the tax incidence ultimately depends on the relative flexibility of buyers and sellers. While most trading partners will attempt to find creative solutions to avoid disruptions in their operations (at least in the short term), the likelihood of disputes is increased in the current environment. Analyzing the underlying economic dynamics is essential for understanding the pressure points within existing contractual relationships.

References

-

This article presents a general analysis framework and does not attempt to provide any policy or legal opinion.

-

US Census Bureau (April 2025). US international trade in goods and services, February 2025 (Release No. CB25-51).

-

Bargaining power also plays a role as smaller companies may risk entering into financial distress if trade is interrupted, increasing the bargaining power of its counterparty.

-

There are 11 Incoterms used in international trade. Only DDP establishes that the exporter is responsible for the payment of tariffs, while the rest transfer the responsibility to the importer. See US International Trade Administration. (n.d.). Know your Incoterms.